Date: 24th February 2019

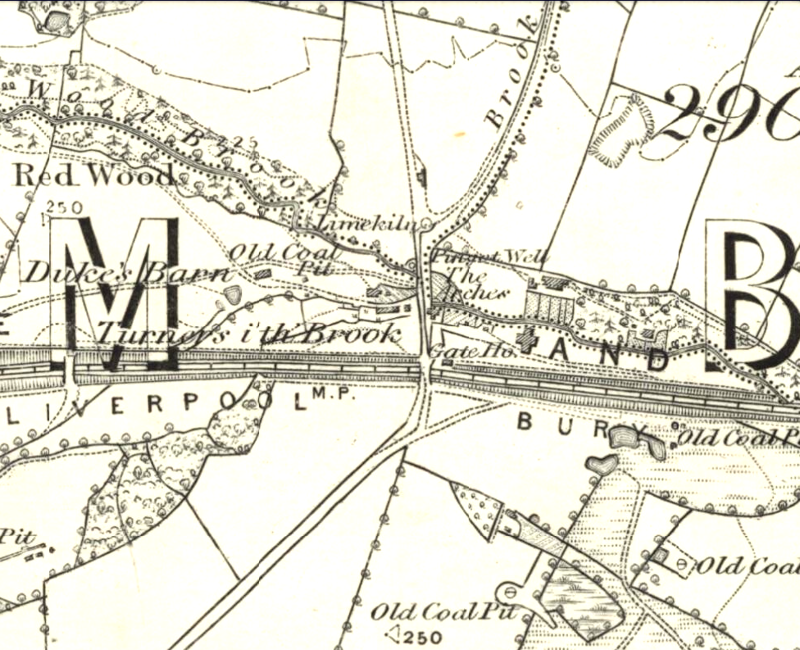

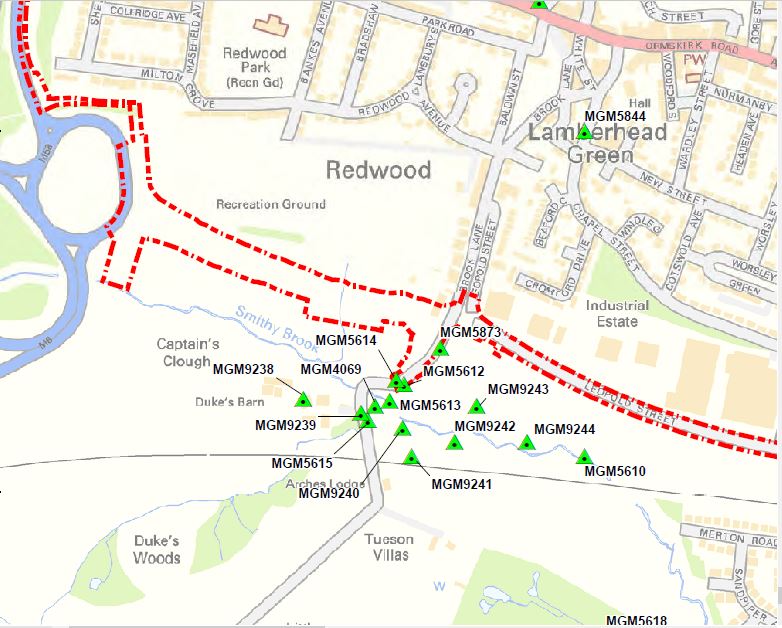

Warm and sunny weather conditions are ideal for drone flying, particularly in the winter months when the vegetation is low. From the 1849 OS map we know Clarke’s wagonroad crossed Ormskirk road at Oldham’s Farm where it changes direction towards Abraham Guest High School (now Dean Trust) before passing Hienz’s factory on its way down to the River Douglas. This area of Lamberhead Green is soon to be transformed by the construction of the M58 Link Road which will bypass it to the south. The road will pass many metres to the north of the Pingot site and therefore will not affect it.

This area of Lamberhead Green is soon to be transformed by the construction of the M58 Link Road which will bypass it to the south. The road will pass many metres to the north of the Pingot site and therefore will not affect it.

The exception however is the remains of the lime kiln at the bottom of Brook Lane (MGM5614 – GM HER 4667.1.0), which could well be destroyed when the lane is re-routed. Its existence has been noted in the planning application so hopefully provision will be made for its recording. The wagonroad appears to go behind the present day Arches Lodge and follow the fence line. The owner has kindly offered to allow us to look for evidence in his back garden. This is an offer we may take up if the opportunity arises.

The wagonroad appears to go behind the present day Arches Lodge and follow the fence line. The owner has kindly offered to allow us to look for evidence in his back garden. This is an offer we may take up if the opportunity arises.

Date: March 29, 2015

This weekend, at short notice, we managed to arrange a field trip to the Pingot site (apologies to those I didn’t manage to contact). We had planned to do this visit at the end of last year but an opportunity never seemed to present itself. Our June Newsletter (No. 174), set out our aims here, which was to find evidence for the Arches viaduct. This structure once carried the Clarkes wagon road over the Pingot valley and was taken down some time in the late 19th century. Our previous survey had enabled us to produce an accurate drawing which we could combine with the old maps. From this we have been able to predict the likely position of the structure’s piers. However our visit in May last year, proved that effective work here could only be achieved when the vegetation was low (i.e. Autumn or early Spring). With time running out this year, we were determined to press on with this project, despite the predicted bad weather.  The rain however couldn’t dampen our enthusiasm, as we could see that the reduced vegetation would give us the best chance of acquiring our sight lines through the undergrowth. It still took a certain amount of pruning before we managed to get a line of ranging poles on the predicted alignment. By studying the maps we could see that the best place to look for surviving pier footings would be at the south end near to the current railway line, as there didn’t seem to be any later development in this area. After some more selective pruning, we could detect a low mound at the right location.

The rain however couldn’t dampen our enthusiasm, as we could see that the reduced vegetation would give us the best chance of acquiring our sight lines through the undergrowth. It still took a certain amount of pruning before we managed to get a line of ranging poles on the predicted alignment. By studying the maps we could see that the best place to look for surviving pier footings would be at the south end near to the current railway line, as there didn’t seem to be any later development in this area. After some more selective pruning, we could detect a low mound at the right location.  Just beyond the railway fence line we spotted this metal object (not sure what it is but got us quite exited for a while as its upturned shape had our imaginations running riot). Probing in this area showed that there was something at about a spade’s depth. However we realised that only an excavation could settle the matter. The land is owned by Tim Bankes who also owns the Winstanley estate but it is not certain whether he would give his permission.

Just beyond the railway fence line we spotted this metal object (not sure what it is but got us quite exited for a while as its upturned shape had our imaginations running riot). Probing in this area showed that there was something at about a spade’s depth. However we realised that only an excavation could settle the matter. The land is owned by Tim Bankes who also owns the Winstanley estate but it is not certain whether he would give his permission.  Whilst on site we decided to have a look at the foot bridge over the railway which is locate behind Duke’s Barn, the farm next to the current road bridge. According to Donald Anderson (The Orrell Coalfield), it was originally part of the viaduct, constructed in 1848 when the Liverpool Bury line was put through. When the viaduct was taken down the bridge was relocated onto its current site. It’s constructed of cast iron, including the parapet, and shows two spans, although it is thought that only the span nearest the camera was used for the viaduct.

Whilst on site we decided to have a look at the foot bridge over the railway which is locate behind Duke’s Barn, the farm next to the current road bridge. According to Donald Anderson (The Orrell Coalfield), it was originally part of the viaduct, constructed in 1848 when the Liverpool Bury line was put through. When the viaduct was taken down the bridge was relocated onto its current site. It’s constructed of cast iron, including the parapet, and shows two spans, although it is thought that only the span nearest the camera was used for the viaduct. The parapet is bolted on using square nuts which must testify to its antiquity (could it have been used on the viaduct itself).

The parapet is bolted on using square nuts which must testify to its antiquity (could it have been used on the viaduct itself). This later edition of the 6 inch OS map shows the viaduct still in place when the Liverpool – Bury railway line was put through in 1848. At that time it was just a single track. The iron bridge was installed to carry Clarke’s wagon road over the railway at the southern end of the viaduct but it shows the foot bridge has also been built over the line. This probably means that the far span in the photo is the original foot bridge span (or even vice versa).

This later edition of the 6 inch OS map shows the viaduct still in place when the Liverpool – Bury railway line was put through in 1848. At that time it was just a single track. The iron bridge was installed to carry Clarke’s wagon road over the railway at the southern end of the viaduct but it shows the foot bridge has also been built over the line. This probably means that the far span in the photo is the original foot bridge span (or even vice versa).  This view from Bing Maps is looking east and shows the foot bridge (bottom of the picture) as well as the current bridge. Just the other side of it is where Clarke’s wagon road crossed the railway. the maps seem to suggest it went round the back of Arches Lodge (the building on the south side of the current bridge). Donald Anderson’s book shows the wagon road going straight across the field on the right. If you look closely you can see a green line where it ran. He dates his map 1818 but on the 1st edition 6 inch map the track is depicted as a tree-lined road going under a wooden bridge carrying the wagon road. The later edition 6 inch map shows it as just a field boundary and on later maps it disappears altogether.

This view from Bing Maps is looking east and shows the foot bridge (bottom of the picture) as well as the current bridge. Just the other side of it is where Clarke’s wagon road crossed the railway. the maps seem to suggest it went round the back of Arches Lodge (the building on the south side of the current bridge). Donald Anderson’s book shows the wagon road going straight across the field on the right. If you look closely you can see a green line where it ran. He dates his map 1818 but on the 1st edition 6 inch map the track is depicted as a tree-lined road going under a wooden bridge carrying the wagon road. The later edition 6 inch map shows it as just a field boundary and on later maps it disappears altogether.

Date: May 25, 2014

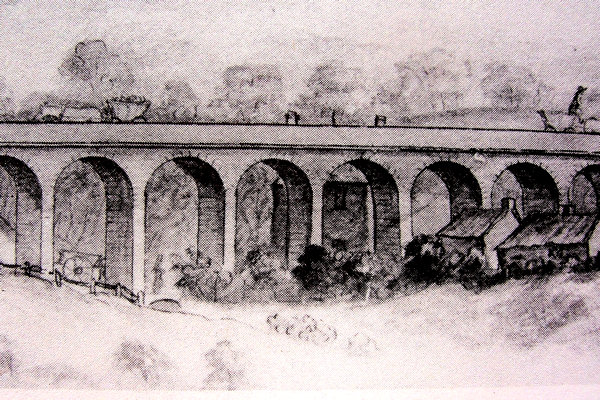

This was our first return to the site in over twelve months. Our purpose was to see if we could find evidence for this structure, which Derek Winstanley described as the earliest viaduct in the world to have carried a steam locomotive. If this is true, it would be a very significant find indeed. Derek had said at our meeting in September that the masonry viaduct (know locally as the Arches) was built by John Clarke in 1792. Clarke, a local mine owner, want to expand mining operations onto the Winstanley Estate. According to Derek’s research, there is no earlier example of a steam engine crossing a stone-built viaduct. Early maps show that viaduct was still in existence when the Liverpool Bury railway line was built in 1848 (a later edition of the 6 inch OS map has the viaduct crossing this line at it southern end). Studying later maps we also discovered that a small community lived in the Pingot Valley for many years, up until the 1950’s when the last buildings were demolished. Our last site visit enabled us to complete a plane table survey of the features still visible (see Newsletter 164). From this we’ve been able to create a detailed drawing combined with maps from the various periods.  Our only image of the viaduct is the sketch looking south east (see February 10, 2013). From it we’ve been able to speculate where its piers would have been located. With this information last month we ventured into the undergrowth. We began by looking at the north embankment near to where the lime kiln is located. Probing indicated that there was stonework just below the surface. However, scraping away the turf in a couple of areas, suggested that this was just loose stones (a gate on the embankment suggested a track had been built here to access the field beyond). We then decided to look at the southern section making our way through dense vegetation.

Our only image of the viaduct is the sketch looking south east (see February 10, 2013). From it we’ve been able to speculate where its piers would have been located. With this information last month we ventured into the undergrowth. We began by looking at the north embankment near to where the lime kiln is located. Probing indicated that there was stonework just below the surface. However, scraping away the turf in a couple of areas, suggested that this was just loose stones (a gate on the embankment suggested a track had been built here to access the field beyond). We then decided to look at the southern section making our way through dense vegetation.  Conditions were difficult (Indiana Jones springs to mind) but we did manage to get a tape across from the present day bridge to relevant area. There was no obvious stonework and probing produced nothing significant. It was felt the test-pitting would be the only option but this would require permission before proceeding. Before we left the site we were able to have another look at the area around the brook and the Pingot Well. The culvert doglegs south for some reason coming out near to where the Manor Farm was. Could there once have been a mill here? It was decided that this area had potential for further study.

Conditions were difficult (Indiana Jones springs to mind) but we did manage to get a tape across from the present day bridge to relevant area. There was no obvious stonework and probing produced nothing significant. It was felt the test-pitting would be the only option but this would require permission before proceeding. Before we left the site we were able to have another look at the area around the brook and the Pingot Well. The culvert doglegs south for some reason coming out near to where the Manor Farm was. Could there once have been a mill here? It was decided that this area had potential for further study.

Date: September 4, 2013

Society meeting – talk by Derek Winstanley on the The Daglish/Clarke Railway. Here is a summary:

‘A VERY SIGNIFICANT MILESTONE IN RAILWAY HISTORY’

The story of the Walking Horse and Clarke’s Railway (by Derek Winstanley)

2013 marks the bicentennial of the first steam locomotive to operate in Lancashire and the third commercially successful one in the world – a very significant milestone in railway history. It was built by Robert Daglish at Haigh Foundry for John Clarke who was a Liverpool banker and owner of Winstanley and Orrell colliery. That locomotive was known as The Yorkshire Horse, or more accurately, The Walking Horse – and it was used to transport coal from Winstanley Hall estate to the canal at Crooke a good 16 years before Stephenson built his Rocket.

For many years in the 18th century, wooden wagonways had been used in the Wigan area to transport coal via horse-drawn wagons from the various coal fields down to the River Douglas. Wagon-loads of coal were transported in controlled descents from the Orrell coalfield, first to the Douglas Navigation in the 1770s and then to the Leeds and Liverpool Canal in 1784. Haulage of loaded wagons uphill was to be avoided because of the excessive strain it put on the horses.

In 1792, John Clarke and hisLiverpoolpartners expanded their operations by leased land from Squire William Bankes of Winstanley Hall and started to mine coal in the estate to the south of Smithy Brook. This brook runs in a valley to the south of Pemberton separating the Winstanley estate from Orrell. The only pathway to transport coal from Winstanley down to the canal at Crooke was to cross Smithy Brook, go uphill toOrrell Road, and then descend through Kitt Green to Crooke. The only way Clarke could achieve this was to build a stone viaduct across Smithy Brook at Pingot, known as The Arches. He was then able to build a horse-powered wagonway from Winstanley to connect with Berry’s earlier wagonway near Oldham’s Fold on Orrell Road, which he had already purchased. It took about 14 horses to pull loaded wagons of coal from The Arches Viaduct up toOldham’s Fold, a distance of about 600 yards. Due to the Napoleonic Wars, the cost of horses and horse feed was high.

In about 1804, Lord Balcarres of Haigh hired Robert Daglish as engineer at Haigh Foundry and Daglish built stationary steam engines to pump water from increasingly deep coal mines. Steam locomotives began to be developed in the early 1800s and in 1812 two steam locomotives were operated successfully ─ on the level ─ at Middleton Colliery in Leeds. About 1810, Clarke planned to expand his coal mining operations in Winstanley and needed to extend his railway to near Longshaw. At this time, he hired Robert Daglish as his colliery manager and Daglish built The Walking Horse, installed fish-belly rails on stone sleepers, and fitted a toothed driving wheel on the left side of the engine to engage with cogged rails. The age of steam locomotives had arrived in Winstanley and Orrell.

The locomotive has been described wrongly by historians as a Blenkinsop locomotive. John Blenkinsop was the manager at Middleton Colliery and he patented the rack system that provided traction for the Middleton locomotives and Daglish’s locomotive. Blenkinsop did not, however, design or build the Middleton locomotives; these were built by the Leeds engine-makers and millwrights Fenton, Murray & Wood. The main reason for calling Daglish’s locomotive The Yorkshire Horse appears to have been the erroneous assumption by many that Daglish simply copied the Middleton locomotives. This assertion also seems to have led many chroniclers to ignore Daglish’s locomotive and perhaps explains why The Walking Horse and the Winstanley-Orrell railway have not been accorded their due places in railway history.

From careful comparison of the Middleton and Daglish’s locomotives and railways, the position of The Walking Horse and Clarke’s railway in early railway history can be established.

- The Walking Horse was

– the first steam locomotive to be built and operate inLancashire;

– the firststeam locomotive in the world to cross a viaduct;

– the first steam locomotive in the world to work successfully for four decades;

– the first steam locomotive in the world to haul loaded wagons up a four percent incline;

– the first commercially successful steam locomotive in the world to have a wrought-iron boiler and chimney and a feed pump;

– the third commercially successful steam locomotive in the world;

– it was two tons heavier and had more horsepower (8 hp) than the first two Middleton Colliery locomotives;

– the tracks had stronger rails (4 ft, fish belly), pedestals and sleepers with chairs fixed by through bolts.

– the Arches Viaduct was the first masonry railway viaduct (c.1790s) in the world and the first viaduct in the world to carry a steam locomotive (January 1813). [Risca Viaduct opened in 1805 and Laigh Milton Viaduct in 1811.] The previous earliest date I can find for a steam locomotive possibly crossing a viaduct is 1816/7, when The Duke was set on rails of the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway, part of which crossed the masonry Laigh Milton Viaduct].

Also, Haigh Foundry was the first foundry and Robert Daglish the first engineer and colliery manager in the world to construct a steam locomotive that operated successfully for four decades. Haigh was the second foundry in the world to construct a commercially successful steam locomotive.

The Walking Horse and Clarke’s railway demonstrated significant improvements in power, reliability, stability and stamina over the Middleton locomotives and railway. These and subsequent improvements in early railways led to the development of mainline railways by 1830. Robert Daglish and John Clarke surely deserve due recognition for their pioneering developments.

References

Derek Winstanley, ‘The evolution of early railways in Winstanley, Orrell and Pemberton, Lancashire, England, 1770s to 1870s’, paper presented at the 5th International Early Railways Conference, Caernarfon, June 2012 [to be published in Conference Proceedings in 2014].

Donald Anderson, The Orrell Coalfield, Lancashire 1740-1850 (Moorland Publishing Co., Buxton, 1975).

Richard Daglish, ‘A YorkshireHorse’, J. Railway and Canal Hist. Soc. 31(3), (1993), 123-31.

————————————————————————

Date: May 19, 2013

This site visit was arranged to establish what features can be recorded and select station positions for a plane table so that we can carry out a survey. Maps supplied by GMAS show that building survived on this site as late as 1955, however not much evidence of these are left on the ground (even the track leading to them could not be identified).  This wall runs on the north side of the brook roughly parallel to it. On the maps, the Pingot well is marked between this and the brook.

This wall runs on the north side of the brook roughly parallel to it. On the maps, the Pingot well is marked between this and the brook. However the culvert under the track is well defined. While we were there the estate warden came to check who we were and to tell us more information about the site. His neighbour, who lives at Duke’s Barn joined us and was able to add more details.

However the culvert under the track is well defined. While we were there the estate warden came to check who we were and to tell us more information about the site. His neighbour, who lives at Duke’s Barn joined us and was able to add more details. Clearing the undergrowth in the area where the well is marked this large stone slab appeared. It appeared to have been moved and underneath was a deep, brick-lined sump with the sound of running water coming from it. Could this be the famous Pingot well? It’s in the right place and the water, running towards the brook, is clear.

Clearing the undergrowth in the area where the well is marked this large stone slab appeared. It appeared to have been moved and underneath was a deep, brick-lined sump with the sound of running water coming from it. Could this be the famous Pingot well? It’s in the right place and the water, running towards the brook, is clear. A sluice on the far side of the sump looks like it could have been used to control the flow (a cast iron pipe can be seen in the bank of the brook where the water is discharged.

A sluice on the far side of the sump looks like it could have been used to control the flow (a cast iron pipe can be seen in the bank of the brook where the water is discharged. Afterwards we set up the plane table near the entrance to the site. This, we perceived, gave us the best view of significant features which could be identified on the OS maps. The following features where then recorded: the north side of the point where the well wall meets the bridge, the culvert entrance, the centre of the culvert exit, the well wall, the west corner of the fence on the embankment. We also recorded the position of the kiln and the north edge of the road in front of it.

Afterwards we set up the plane table near the entrance to the site. This, we perceived, gave us the best view of significant features which could be identified on the OS maps. The following features where then recorded: the north side of the point where the well wall meets the bridge, the culvert entrance, the centre of the culvert exit, the well wall, the west corner of the fence on the embankment. We also recorded the position of the kiln and the north edge of the road in front of it.

Date: February 10, 2013

Web searching revealed these two images of the Arches viaduct. Judging from the 1849 OS map, the sketch is looking east with cottages on the south bank of the brook – a large building behind the viaduct which is probably Arches Farm. The well would have been on the left in front of the viaduct on the north bank. A cart is shown ready to load up with water from the well – also notice the cart on the the bridge loaded with coal from the Winstanley estate being pulled by a horse (and an empty one going back).

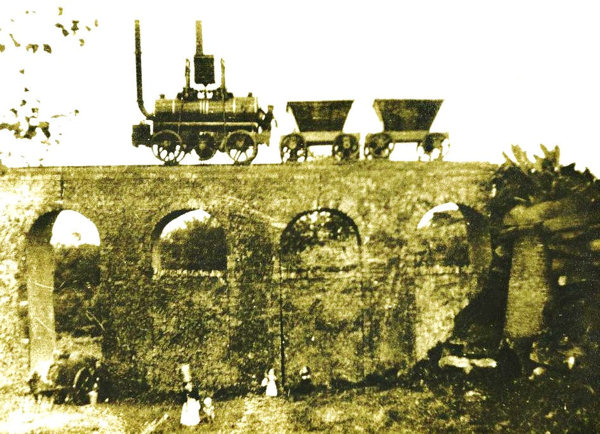

Judging from the 1849 OS map, the sketch is looking east with cottages on the south bank of the brook – a large building behind the viaduct which is probably Arches Farm. The well would have been on the left in front of the viaduct on the north bank. A cart is shown ready to load up with water from the well – also notice the cart on the the bridge loaded with coal from the Winstanley estate being pulled by a horse (and an empty one going back). This image, seemingly taken from the other side, is a famous composite photo showing the Yorkshire Horse (or a model of it) on the viaduct. This early steam engine, which predated Stephenson’s Rocket, was built by a Scottish engineer called Robert Dalgleish who work at Haigh Foundry. What is interesting about this photo, however, is that it shows the kiln tucked away on the right hand side – also the first 3 arches seem to be walled up for some reason (it turns out that even the viaduct is probably fake).

This image, seemingly taken from the other side, is a famous composite photo showing the Yorkshire Horse (or a model of it) on the viaduct. This early steam engine, which predated Stephenson’s Rocket, was built by a Scottish engineer called Robert Dalgleish who work at Haigh Foundry. What is interesting about this photo, however, is that it shows the kiln tucked away on the right hand side – also the first 3 arches seem to be walled up for some reason (it turns out that even the viaduct is probably fake).

Date: November 18, 2012

Site visit arranged to evaluate potential for future work. After parking up at the bottom of Brook Lane we soon spotted the stone arch protruding from the embankment. It is obvious that there is not much left of the old kiln but it was our opinion that it should be at least recorded. It is also at this spot on the old map where an old colliery line is shown crossing the Pingot Valley. It was supported on a viaduct know as The Arches. This line was famous for carrying the Yorkshire Horse – a steam engine dating to the early 1800′s which transported coal from the Winstanley estate down to the River Douglas.

It is also at this spot on the old map where an old colliery line is shown crossing the Pingot Valley. It was supported on a viaduct know as The Arches. This line was famous for carrying the Yorkshire Horse – a steam engine dating to the early 1800′s which transported coal from the Winstanley estate down to the River Douglas. With this in mind we entered the undergrowth on the other side of the lane to see if we could spot any remains of the viaduct in this area. There is stonework which is on the right alignment where the Smithy Brook enters a short culvert. There are also large lumps of concrete and a low wall where a well is indicated on the OS map.

With this in mind we entered the undergrowth on the other side of the lane to see if we could spot any remains of the viaduct in this area. There is stonework which is on the right alignment where the Smithy Brook enters a short culvert. There are also large lumps of concrete and a low wall where a well is indicated on the OS map. Census records indicate that there was a small community living here in varies cottages in the mid 19th century (nine households with a total of forty-six people listed). The Pingot Well is also said to have been the only decent supply of water in Pemberton and there was a near riot when the council closed it 1880 (more details of this was available on the Wiganman website but for some reason this website, which was extensive and quite useful, was taken down in March 2013). Our trip proved that the the site has good potential for further investigation and worth setting up a project here to see if we can identify and record some of the feature which date back at least to the late 18th century.

Census records indicate that there was a small community living here in varies cottages in the mid 19th century (nine households with a total of forty-six people listed). The Pingot Well is also said to have been the only decent supply of water in Pemberton and there was a near riot when the council closed it 1880 (more details of this was available on the Wiganman website but for some reason this website, which was extensive and quite useful, was taken down in March 2013). Our trip proved that the the site has good potential for further investigation and worth setting up a project here to see if we can identify and record some of the feature which date back at least to the late 18th century.

“I was back in Wigan in May and discovered that the remnants of the old lime kiln at the bottom of Brook Lane in Pemberton are still there. This was by the side of the Arches Viaduct that carried the Yorkshire Horse across Smithy Brook. I presume the lime kiln was built to facilitate construction of the viaduct, probably in the 1790s. Would WAS have any interest in excavating and/or preserving this?”

It is shown as a Limekiln on the 1849 first ed 6″ OS map – and it is also recorded in the SMR as being extant in 1785 (not sure on what evidence) – the SMR also says there are no visible remains. The Pingot valley is very interesting from an industrial archaeological point of view. It would be interesting to discovery if it is really a lime kiln – the only way to find out would be to excavate (but would need to find out who it belongs to first).

The Pingot valley is very interesting from an industrial archaeological point of view. It would be interesting to discovery if it is really a lime kiln – the only way to find out would be to excavate (but would need to find out who it belongs to first).

Hello from New Zealand

Interesting stuff on the Pingot Valley

I have an ancestor who came to NZ in 1852 and proclaimed to be a tradesman ropemaker having worked in a ropeworks factory with an address of :-

Edward Thomas & Son Ropemakers

Pingot Lane ropery, Hyde, Cheshire

It is likely he was the son of the owner another Edward Thomas.

He never made a foot of rope while he spent the rest of his life here in Christchurch NZ!

Do you have any knowledge of an early ropeworks of this name around this district? There is a suggestion it went out of business in 1863 with the cotton crisis.

Cheers

Pat Thomas

Christchurch,NZ

Hi Pat – I haven’t come this name before but, judging from the 1849 OS map, there were plenty rope makers in the Wigan area.

Bill

Hi Bill

Thanks for having a look at this

Cheers

…but a ropery in Hyde would be a good way away from Wigan. Hyde is 24 miles away as the crow flies. There is still a Pingot Lane out there, but it’s beyond Hattersley, making it over 30 miles from our site, and certainly nothing to do with the Pingot Valley in Wigan.

Patrick

Chairman, Wigan AS

Thank you so much for publishing all this information. It has been a revelation to me. My family history researches show that a number of my relatives lived in ‘The Arches, Pemberton’ from the 1840s onwards and worked down the Pemberton pits, and in the mills, but I had no idea what and where The Arches were till now. I’m so delighted to discover the historical significance of Pingot’s Well, the viaduct and the surrounding area. I searched a few years ago for information without luck, but I tried again, and bingo, you have shared your knowledge! I know what time and trouble it takes constructing web pages, so again a big thank you.

Hi Elaine,

Thanks for the feedback – hopefully this year we will be making a return visit to the Pingot site to see if we can locate the position of the Arches viaduct and perhaps find some of its remains. We would also be very interested in details of any of the families that lived in the valley.

Thanks again

Bill Aldridge

(secretary)

Hi Bill,

I’ve just been looking at the WAS website and found this correspondence. Like Elaine, I also have several members of my family in my direct line living in The Arches in the mid 19th. century. If you’re still interested in this, let me know what sort of detail you want and I’ll email it to you.

Best wishes,

Helen

Hi Helen, yes we would be interested in any details of the people living in The Arches in the mid 19th century. It was later know as Arches Farm and eventually Manor House Farm. There was also a row of cottages which appear on the sketch of the viaduct. We think these were replaces by a single dwelling called Pingot House or Pingot Cottage. We’re currently not doing any work there at the moment but in the near future we are hoping to carry out more investigations including searching for the foundations of the viaduct. Please send any information you have to this e-mail address bill@wiganarchsoc.co.uk – cheers

Fascinating exploration. I see the map marks a “wooden bridge” just south of the Arches. This was presumably on the route of the railway, and staring at Google Maps with not too much eye of faith, there appears to be a soil mark, slightly lighter in colour than the surrounding ploughed soil, running diagonally NE to SW from the sharp turn on Hall Lane to the house by Workshop Wood. As it’s possible that the field is currently again in a ploughed state just now, I wonder if it would be worth a quick field walk along the mark to see if anything has been turned up? Sadly, I’m not in the Wigan area.

I can see what you mean. On the 1st edition 6 inch OS map of 1849 there is a road shown quite prominently going off in the direction you mention – but it’s a road not a railway – on the map it’s called Coal Pit Lane. It didn’t last long however as on a later edition 6 inch map, the road is shown as a field boundary. By 1893 even this boundary has disappeared. Both Google and Bing maps do seem to show a lighter green mark along the line of the road but we have look many times in that field and failed up to now to spot anything (maybe worth another look in light of the crop mark).

But is it a road? Though it’s tree- lined, pointing possibly to a carriage drive associated with the Winstanley Hall estate, it doesn’t go anywhere (except to the Arches), and you’d expect an ornamental bridge of stone or brick and iron as a visual feature. It’s actually specifically identified as a “wooden” bridge. I see no sign of the railway either, though if the locomotive lasted about 40 years, the line should still be in use in 1849, or only recently disused. Is it possible that a conventional sign for a mineral line had not developed by that date, or that a later revision of the map engraving simply removed the railway? I note that Sanderson’s map of 1835, “Twenty Miles Around Mansfield” (much more my area) shows railways as simple hatched parallel lines.

The later disappearance isn’t at all surprising. Mineral lines commonly held wayleaves, paying an annual rent for the land traversed, and once the wayleave expired the landowner would simply take possession and reincorporate the (usually lightly built) formation into their own farm, park or whatever – the area is marked as parkland on the 1896 OS one-inch map.

Just one more point- you refer to te “Walking Horse”, whereas the appendix on the locomotive in Part 2 of “The Industrial Railways of the Wigan Coalfield” seems to imply that there were two in operation.

Anyway, keep up the excellent work, and in the meantime I’ll have to chase up those references to the railway. I have a passion for early railways, living withing striking distance of the “world’s first”- Huntingdon Beaumont’s pioneering work of 1604 near Wollaton, Nottingham.

My thought is that the dotted lines (shown on the 1849 map) mark the route of the railway (now called Hall Lane). It went over the road (Coal Pit Lane) on the wooden bridge just south of the viaduct. Coal Pit Lane might have originally been a wagon road but seems to miss the viaduct on the west side going down into the valley – with a steep climb on the other side. Donald Anderson does show it as a railway however in his book on the Orrell Coalfield. We are planning another visit soon so hopefully we’ll find out more about this fascinating area. By the way Daglish built three engines for this line – two in use and one being serviced (two had sprocket drive wheels similar to Blenkinsop’s – the other just relied on adhesion with the rails).

i have been reading the above and found it very interesting and remarkable as i live 10 mins away from brook lane etc. can any body tell me if this is protected land from buliding work?? and if so where could i obtain a copy. thanks helen pemberton community association. thankyou

Hi Helen – as far as I’m aware the land isn’t protected. The area we are interested in is included in the Winstanley Estate which is own by the absentee landlard,Tim Bankes (the new road development in to the north of the the brook which I don’t think is on his land).

Hi I live on the new housing estate built next to the arches, what significance did this land have in relation to the arches.

It’s really interesting and fasinating to live close by to something so historical.

Hi Carmen,

I assume you mean the estate to the east of Brook Lane. In the 18th century there was a cluster of coal pits in the area owned by Clarke and Hawarden. The whole scene was an industrial lanscape.

Hope this helps,

Bill Aldridge

Hi

I don’t suppose you know who owns the original to that picture of the model on teh viaduct? i want to ask whether I can use it in a museum display on very early locomotives!

Hi Terri – I don’t know who owns the original but I do know it appears in Donald Anderson’s book on the Orrell Coalfield. It’s a shame it isn’t an image of the Walking Horse that Daglish built which was a bigger engine. A couple of years ago Derek Winstanley had a drawing commissioned based on the details supplied by a descendant of Daglish, I could ask him if you can use it.

Hi i live in this area and often dog walk this area too

Alot of it is private land but is so intruiging i just wanna know more and more about this .wigan has already lost alot of its historical places and what ive just read of your blog should be in history books.

I had a walk over the little brook and footbridge to the small wooded area were you said and found some old iron buckets or large bowl and riveted water tank

I guessed their old but didnt think could be of that age .

Truely fixated on the area as many mines and shafts and winstanley hall and the railways and stonework is just amazing keep up your efforts truely amazing.

Cheers Scott for your kind words. Regarding the Link Road, Norman Redhead from Gtr Man Archaeology Advisory Survey has been in touch. He says that there will be archaeological investigation on the route of of the Wagon Road and the Kiln Site before work on the Link Road begins (which is good news).

I have just inherited some paperwork following the death of my Mum and apparently my Great Grandfather Thomas Gerrard sold water from Pingot Well ( he transported it in a handcart.)Does this sound likely? At age 25 he was listed as a coal miner of Lamberhead Green.