Index:

Introduction

____Resistivity Survey

Season 1 (2022)

Excavations

____Termini

Research

C14 Dating

Season 2 (2023)

____Coring Survey

Excavations

____Termini __Interior__Sandy Clay Mound__Grooved Stones

C14 Dating

Season 3 (2024)

____Fossil Stones __Coring Survey

Excavations

____Trench 1b to 3a __Trenches 3b and 3c

____Central Area Sections __Octagonal Feature __Possible Cist

____Trench 3a NE Side __Trench 3a SW Side

Drawings (Season 3)

Ring Ditch Work

Season 4 (2025)

Further Ring Ditch Work

____Trench 1__Trench 6/6a__Trenches 5/5a and 7

____Trench 3d__Trench 10

Central Area Excavations

____Clay-Lined Feature__Trench 3a SE__Possible Cist Area

____Two Slabs Burial__Token Burials

Urn Removal

____Urn 1__Urn 2

Circular Alignment Feature

Drawings (Season 4)

Our Site Diaries detail our daily progress over each year,

for Season1 (2022)

for Season2 (2023)

for Season3 (2024)

for Season4 (2025)

Introduction

We first became aware of this site when Steven Twigg (formally of STAG – South Trafford Archaeology Group) contacted us in 2019 with an aerial image he’d spotted in a field in Aspull. The crop mark showed up quite clearly as a dark green circle and seemed to represent a circular ditch around 40m in diameter. Viewing various other aerial images spanning a number of years confirmed the mark to be more than just a temporary agricultural feature. The size of the circle suggested something prehistoric and probably older than Iron Age as it was certainly bigger than a roundhouse typical of this period. Our excitement grew when the LiDAR image revealed the crop mark to have a shallow mound in the centre. This was pointing towards a Bronze Age barrow, although quite large (similar sized ones though do exist mainly in the South, examples can be seen at Normanton Down in Wiltshire). Its central mound and continuous surrounding ditch was suggesting a Type 2 Bowl Barrow as classified by Historic England (ref).

The size of the circle suggested something prehistoric and probably older than Iron Age as it was certainly bigger than a roundhouse typical of this period. Our excitement grew when the LiDAR image revealed the crop mark to have a shallow mound in the centre. This was pointing towards a Bronze Age barrow, although quite large (similar sized ones though do exist mainly in the South, examples can be seen at Normanton Down in Wiltshire). Its central mound and continuous surrounding ditch was suggesting a Type 2 Bowl Barrow as classified by Historic England (ref).

Other features were also noted on the LiDAR image. About 230m to the south on the other side of the road leading to the Farm, another larger circular mound can be seen. This is quite visible on the ground, but its size would suggest that it’s a natural feature probably a product of glacial activity. A linear feature runs for 370m (or perhaps more) diagonally to the northwest just 50m north of our ring feature. This feature seems to relate to an old field boundary which show up on early maps.

The ring feature site lies in an open field which gently slopes towards the east. From the site, there are extensive views over the fields towards Bolton to the east (the Wanders football stadium can be seen in the distance lying at the foot of Winter Hill). To the northeast are the moors of Anglezarke and Winter Hill where prehistoric sites are know. In the middle distance, Borsdane Brook runs from north forming the boundary of the Wigan Metro Borough. On our first site visit, we were able to talk to the landowner who showed great interest and allowed us to wander over the field. We attempted drone imaging, but this failed to detect anything. However, the shallow mound was just about discernible on the ground.

The pandemic in 2020 stopped any further activity but in May 2021 Chris Drabble carried out a comprehensive aerial drone survey. This revealed a dry central circular area, 23m diameter rising to a height of 1.4m and surrounded by a further damper area 6.5m wide. This seemed to confirm that the feature is man-made.

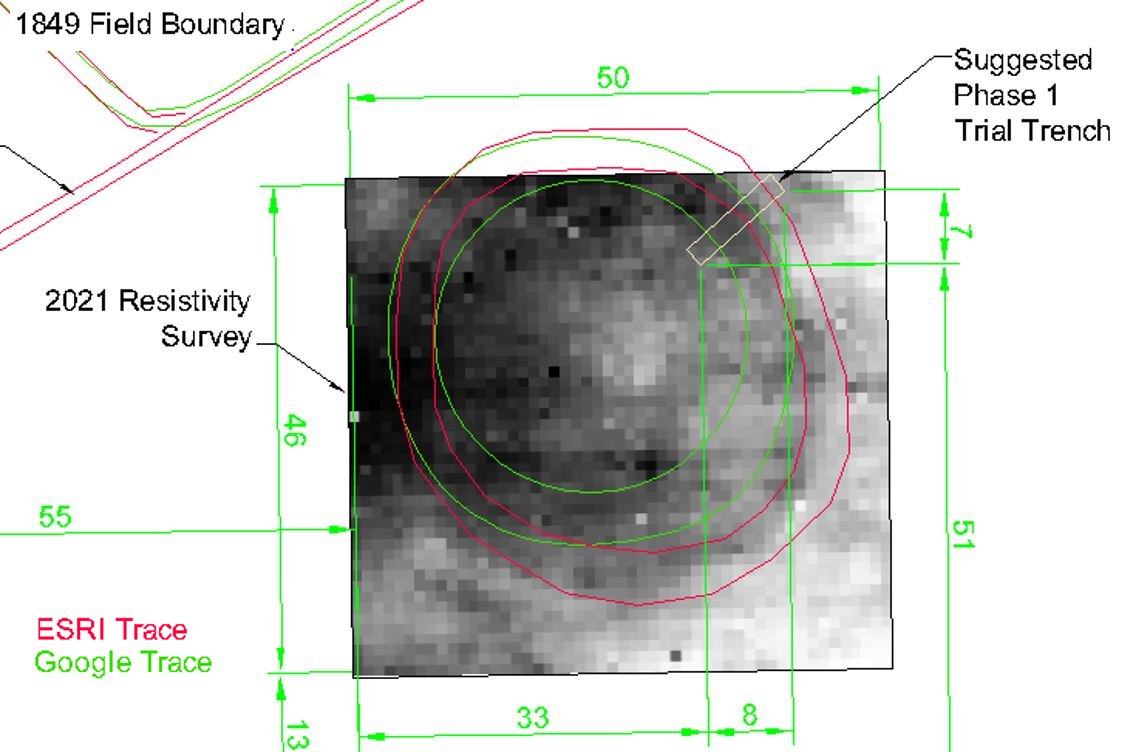

Resistivity Survey. In the Autumn of 2021, we carried out a resistivity survey of the site with very encouraging results as reported in our October Newsletter (No.246). Our two scans covered an area 50m x 46m and revealed the existence of below-ground archaeology in the form of a huge circular feature roughly corresponding to the aerial imagery, with central targets and possible outer bank in the southwest corner.

The next step would be to carry out some form of excavation but first we needed a Project Plan to know how this would be undertaken by setting out our aims and objectives and formulating a methodology. We envisaged that excavations would be carried out in phases, the first phase being an exploratory trial trench (no more than 2m x 11m) across a section of the circular feature. The suggested position would cover a rare area where crop marks from both the Google Earth and ESRI aerial images more or less coincide with the result from our resistivity survey. The second phase would be to determine the extent of the ring ditch (if that’s what it was) by putting more trenches in areas where we expected the ditch to be. The final phase would be to explore the interior to find out the nature of the mound i.e. if it’s manmade or natural and if manmade, its purpose (was it a funerary monument or just ritual).

The second phase would be to determine the extent of the ring ditch (if that’s what it was) by putting more trenches in areas where we expected the ditch to be. The final phase would be to explore the interior to find out the nature of the mound i.e. if it’s manmade or natural and if manmade, its purpose (was it a funerary monument or just ritual).

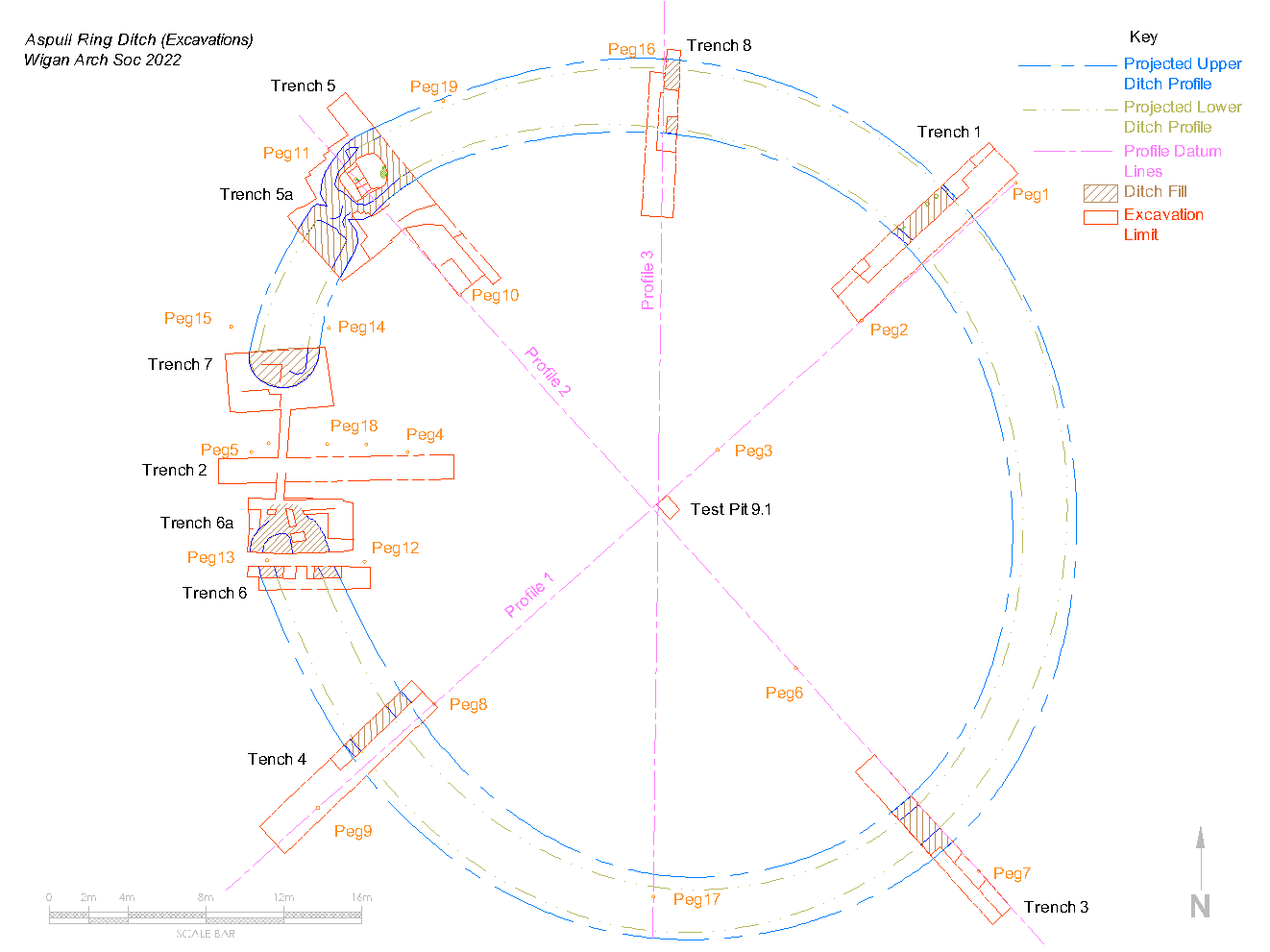

Excavations (Season1) (Return to Index)

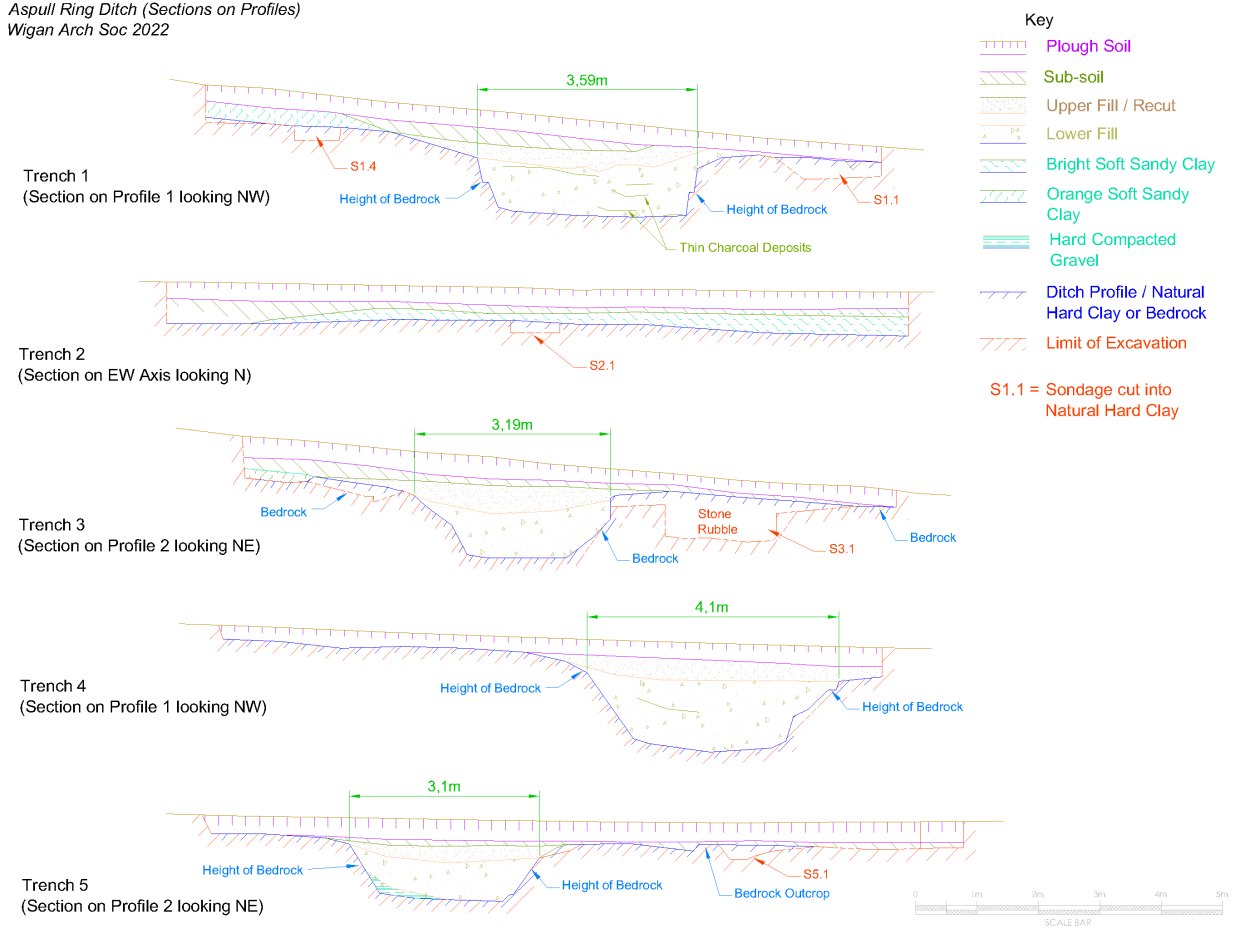

Phase 1. We started work early in 2022 and, fortunately for us, we had a farmer who was not only as keen as we are to find out what is in his field, but also quite obliging when asked to help with removing the topsoil for us. As soon as this was done, we were able immediately to detect a colour change in the sub-soil indicating the location of the ditch. A few visits later and we had the whole ditch section exposed. This revealed it to be huge – over 3.5m wide and 1.5m deep. To our surprise, the steep sides had not only cut through the hard clay, but also bedrock leaving a flat bottom almost three metres wide. The section revealed two layers of soft sandy clay material filling, showing a recut or perhaps two periods of backfilling (or even just settling of the first fill).  Strangely though, apart from this, and the odd thin band of dark material, there were no signs of silting and the floor was generally clean suggesting the ditch was not left open to fill naturally, but backfilled in a single session. Without any finds, we couldn’t put a date on it, although the size of the ditch would tend to suggest something Neolithic rather than Bronze Age. A thin band of dark material from the very bottom of the ditch produced a small piece of charcoal large enough to get a carbon 14 date. With funding from CBA NW, this was duly sent off to the labs in Oxford, but it was towards the end of the year before we received the result. To our surprise this came in at 1501 (95.4%) 1425 cal BC i.e. mid Bronze Age – however it did confirm that we had a prehistoric ditch which was the aim of our first phase.

Strangely though, apart from this, and the odd thin band of dark material, there were no signs of silting and the floor was generally clean suggesting the ditch was not left open to fill naturally, but backfilled in a single session. Without any finds, we couldn’t put a date on it, although the size of the ditch would tend to suggest something Neolithic rather than Bronze Age. A thin band of dark material from the very bottom of the ditch produced a small piece of charcoal large enough to get a carbon 14 date. With funding from CBA NW, this was duly sent off to the labs in Oxford, but it was towards the end of the year before we received the result. To our surprise this came in at 1501 (95.4%) 1425 cal BC i.e. mid Bronze Age – however it did confirm that we had a prehistoric ditch which was the aim of our first phase.

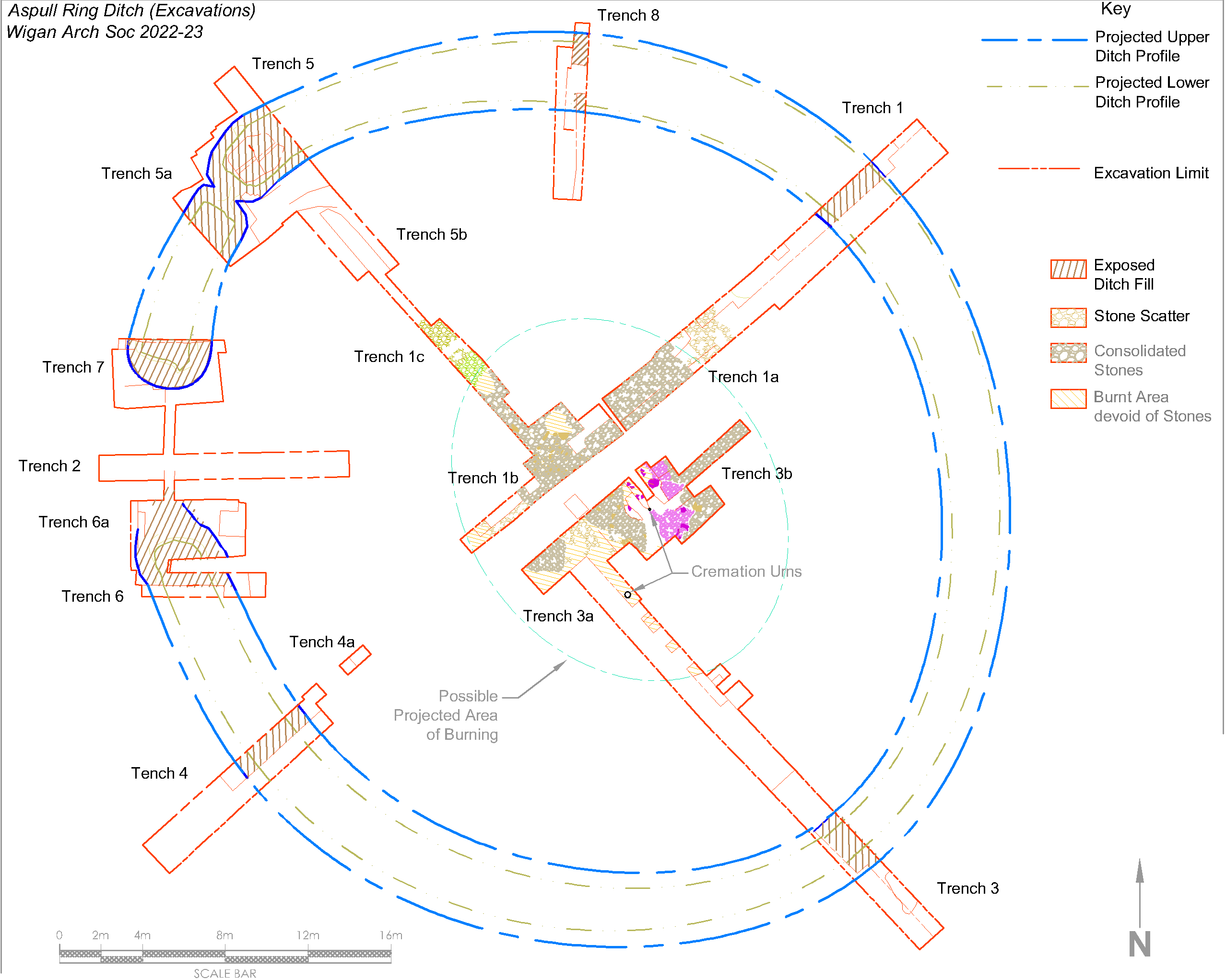

Phase 2. For our second phase we selected our next trench in an area where the images and survey results were less clear, i.e. on the westside quadrant of the circle. To our big surprise, Trench 2 revealed nothing apart from sub-soil and a layer of soft sandy clay lying on top of the hard natural clay. We were greatly relieved therefore when Trench 3 (dug on the southeast quadrant) revealed the tell-tale colour change in the sub-soil. When fully dug out, gratifyingly it revealed the same structure as in Trench 1 i.e. rock cut with a flat bottom (albeit slightly smaller at 3m wide but slightly deeper at 1.6m).  Trench 4, dug on the southwest quadrant, once again revealed the same trapezoidal shape, only this time bigger than Trench 1 (almost 4m wide) and deeper than Trench 3 (at 1.75m). Again, there were no signs of layering or silting apart from the dip of a secondary fill. We now had three confirmed ditches, all cut into the natural hard clay and underlying bedrock. Assuming our feature to be a perfect circle, we located our next trench (Trench 5) in an area where we expected the ditch to be in the northwest quadrant. Things again did not go to plan however as our ditch turned out to be as much as 5m further out from where we expected it to be (and frustratingly under our spoil heap). After moving this, our excavation once again revealed the usual shape but slightly smaller than the rest at just over 3m wide and 1.3m deep.

Trench 4, dug on the southwest quadrant, once again revealed the same trapezoidal shape, only this time bigger than Trench 1 (almost 4m wide) and deeper than Trench 3 (at 1.75m). Again, there were no signs of layering or silting apart from the dip of a secondary fill. We now had three confirmed ditches, all cut into the natural hard clay and underlying bedrock. Assuming our feature to be a perfect circle, we located our next trench (Trench 5) in an area where we expected the ditch to be in the northwest quadrant. Things again did not go to plan however as our ditch turned out to be as much as 5m further out from where we expected it to be (and frustratingly under our spoil heap). After moving this, our excavation once again revealed the usual shape but slightly smaller than the rest at just over 3m wide and 1.3m deep.

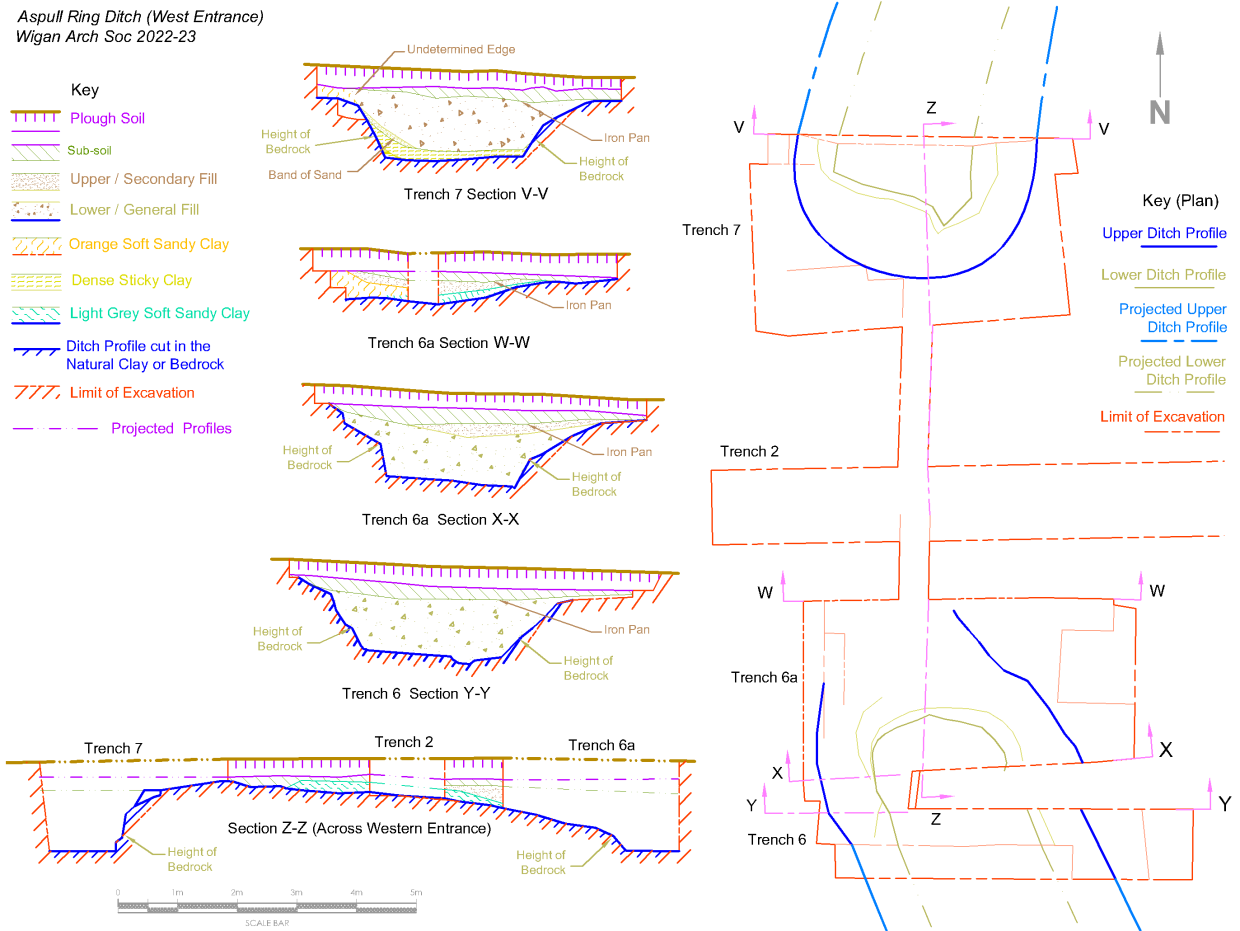

Termini. We were aware now that our feature was not perfectly circular and had a possible entrance on the west side. This, together with the size of the ditch, was strengthening our conviction that this was something old than Bronze Age, a Neolithic henge perhaps. However, there were no signs of an outer bank and we had a mound on the inside (something not normally associated with henge monuments).

But was there an entrance? – if the feature was oval-shaped, had we just missed it? Our next trench (Trench 6) therefore was located just a few metres south of Trench 2 where our entrance was perceived to be. Straight away, signs of the ditch appeared exactly where we expected it to be on the circular projection. Without fully digging it out, we moved straight on to open a larger area (Trench 6a) further towards Trench 2. Gratifyingly this produced the expected shape of a ditch terminus which, when fully excavated, revealed it be semi-bowl shaped (well, almost).  The only sign of bedrock was at the bottom of the trench so it was difficult determining the exact profile. This was particularly true at the very end where there was evidence of extensive tree-root damage (further investigations of this area produced what appeared to be a slope leading into the ditch).

The only sign of bedrock was at the bottom of the trench so it was difficult determining the exact profile. This was particularly true at the very end where there was evidence of extensive tree-root damage (further investigations of this area produced what appeared to be a slope leading into the ditch).

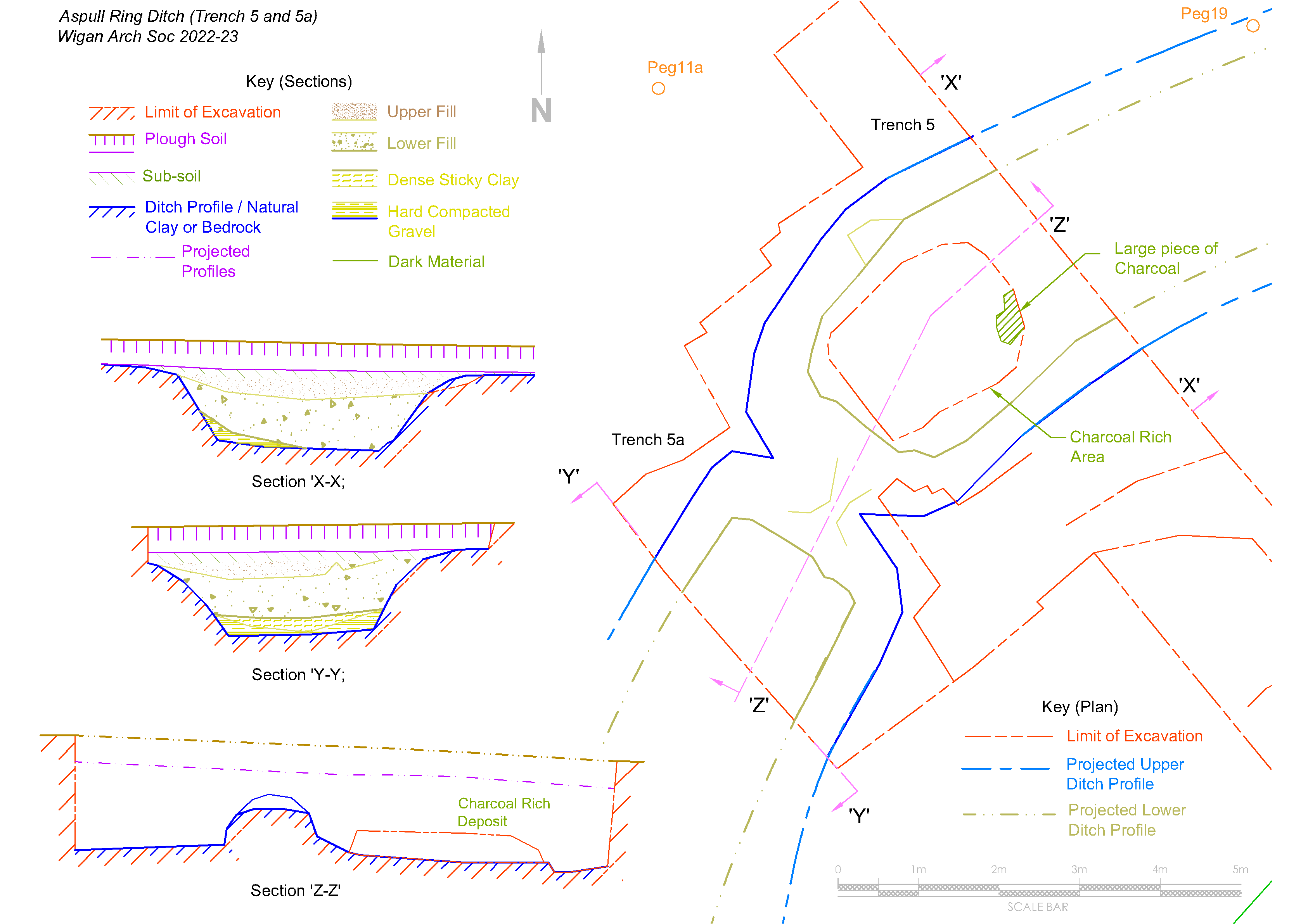

We were now confident we had an entrance, so we began to look for the north-side terminus. By now we were using an auger (a 20mm by 1m long screw) to give us some indication where to look. We planned to chase the ditch from where we had found it in Trench 5 towards Trench 2. Augering however can be misleading, particularly where the ground is stony, as was the case in the area next to Trench 5. This led to us digging our next trench (Trench 5a) right next to Trench 5 thinking this was where the terminus was (although we knew this was strange, as it would have made the entrance huge). Fortunately, this turned out not to be the case but it did reveal something even stranger. When the two trenches were expanded and joined together, to our surprised we found a junction of two ditches. When the profiles were fully excavated, the ditches seemed to be slightly out of alignment and even stranger, revealed to be square ended.

Using the auger, with due diligence this time, we located our next trench (Trench 7) a lot closer to Trench 2. This thankfully revealed the north-side terminus showing the entrance to be 6.5m wide. As with the south-side terminus, our initial investigations showed it to have a semi-bowl shape profile but this time there was no sign of an access ramp. Our last trench (Trench 8) was dug on the north quadrant just to confirm the shape of the feature in that area.

Using the auger, with due diligence this time, we located our next trench (Trench 7) a lot closer to Trench 2. This thankfully revealed the north-side terminus showing the entrance to be 6.5m wide. As with the south-side terminus, our initial investigations showed it to have a semi-bowl shape profile but this time there was no sign of an access ramp. Our last trench (Trench 8) was dug on the north quadrant just to confirm the shape of the feature in that area.  We now had a clear picture of our monument, i.e. it was slightly oval-shaped with an entrance on the west side and a junction between two separate sections on the northwest axis. There could well be more junctions but this could only be determined by opening more trenches (augering not being particularly reliable).This concluded our first season of digging on this remarkable site. Next season would involve investigating the central area but you can see much more detail of this year’s work on our Site Blog Diary here .

We now had a clear picture of our monument, i.e. it was slightly oval-shaped with an entrance on the west side and a junction between two separate sections on the northwest axis. There could well be more junctions but this could only be determined by opening more trenches (augering not being particularly reliable).This concluded our first season of digging on this remarkable site. Next season would involve investigating the central area but you can see much more detail of this year’s work on our Site Blog Diary here .

Research (Season1)

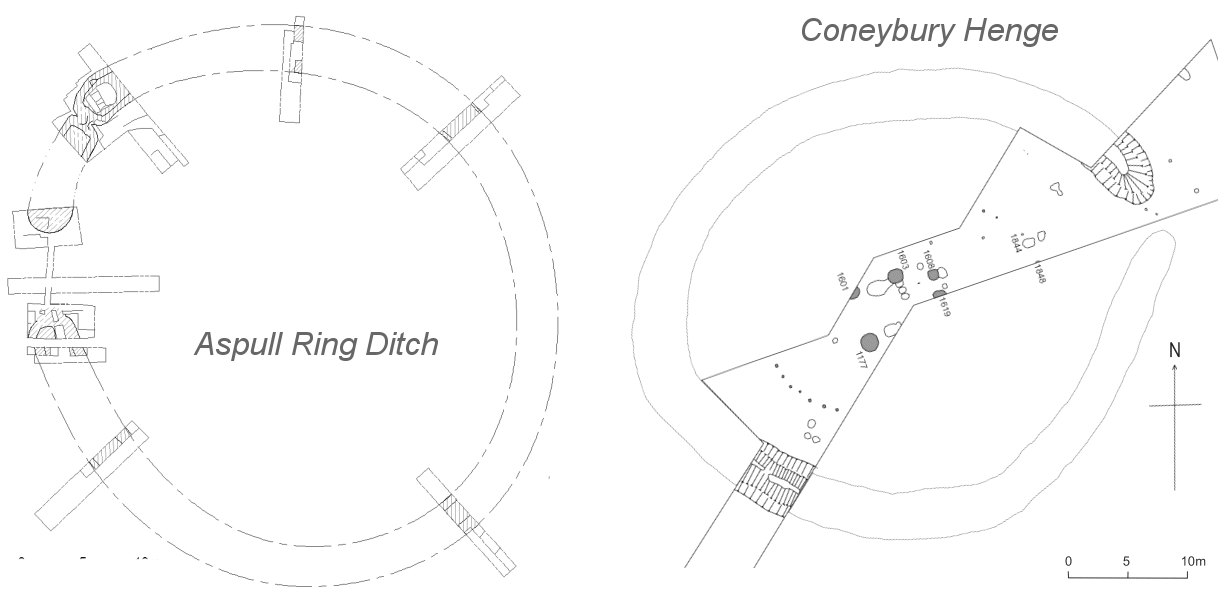

During the closed season we continued our research to try to understand what we had discovered. Apart from the charcoal giving us our C14 result, we had no other finds, so we were relying on typology alone. However this was not easy, as there did not seem to be many sites of similar size and form. We did find sites with similar configurations to ours known as causewayed ring ditches. A group of these in North Wales had one in particular at Pentrehobin, that had similar proportions to ours with a 44m diameter, 4m wide by 2m deep ditch (W. J. Britnell and N. W. Jones – Archaeologia Cambrensis 161 (2012), 165–198). Another group on the Isle of Thanet in Kent, excavated in the 1970s and 80s, had one called Lord of the Manor III, which had a central mound like ours. Perhaps the closest proportionally to ours though is a site not far from Stonehenge called Coneybury henge (Richards 1990).  As with ours, it has no outer bank (which is assumed to have been ploughed out) but unlike ours it didn’t have a central mound.

As with ours, it has no outer bank (which is assumed to have been ploughed out) but unlike ours it didn’t have a central mound.

All these sites are generally dated to the late Neolithic / early Bronze Age and some contain burials, but rarely have central mounds. When these do occur, it suggests maybe a transition period when the newcomers reused the old monuments, before building their own traditional ring ditches and barrow forms.

C14 Dating (Season1). As mentioned before, our first result from Trench 1 came in at 1501 (95.4%) 1425 cal BC. Towards the end of year we were ale to retrieve two more samples of burnt wood which were duly sent off for testing. This time they had been retrieved from the bottom of Trench 5 from what appeared to be a small cairn made of alternating layers of stone, clay and sand. One sample went to the Chrono14 labs at Queens University Belfast, the second to CARD which a free service specifically set up for amateur groups. The result from Queens gave a calibrated Median Probability – 1648 BC and from CARD – 1687 (95.4%) 1535 cal BC. Although the dates range over 200 years, it’s still in the mid Bronze Age range. CARD identified the wood species as oak, which they say is less accurate than say willow which has a much shorter life span. It must be remembered though that all these dates indicate when the ditch was last open, not when it was constructed (which suggests that the ditch had been maintained by the Bronze age people)

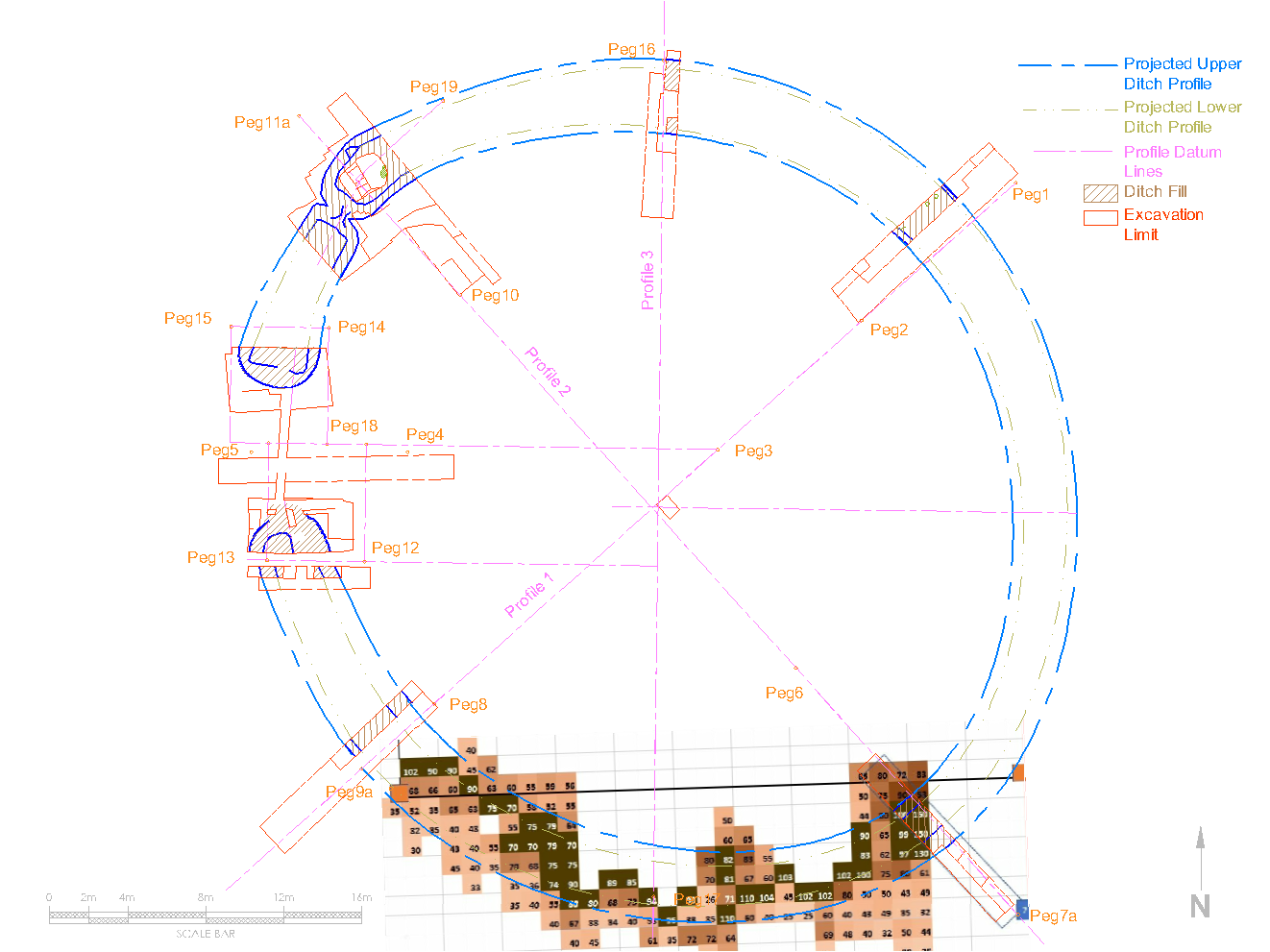

Coring Survey (Season2). Work started early in March with a coring survey on the southern quadrant between Trenches 3 and 4. This was an experiment to see if we could detect the ditch and whether it continued or were there any gaps of junctions similar to Trench 5/5a. We used a one metre long 20mm diameter corer on a one metre grid and the result proved quite positive. We were able to confirm that in this quadrant there were no large gaps although there was the possibility of a junction which we could investigate at a later stage.  With this success our intention will be to do another when we get chance on the east quadrant where, if there is another entrance, that’s the most likely location (i.e. opposite the west entrance).

With this success our intention will be to do another when we get chance on the east quadrant where, if there is another entrance, that’s the most likely location (i.e. opposite the west entrance).

Excavations (Season2) (Return to Index)

Termini. Before starting on the central mound we had some unfinished work to do in the ditch terminals. In Trenches 6 and 6a (on the south side of the entrance) we final joined the two together revealing a fine bedrock floor.  Similarly in Trench 7 on the north side of the entrance the bedrock floor was also revealed. This showed that, although the upper section of the terminal was semi-bowl shaped, the lower section was squared off similar the the other end of this ditch section in Trench 5a.

Similarly in Trench 7 on the north side of the entrance the bedrock floor was also revealed. This showed that, although the upper section of the terminal was semi-bowl shaped, the lower section was squared off similar the the other end of this ditch section in Trench 5a.  However is was becoming less certain about the original ground surface on the external side of the ditch in both these areas, something which needs further investigation at a later date.

However is was becoming less certain about the original ground surface on the external side of the ditch in both these areas, something which needs further investigation at a later date.

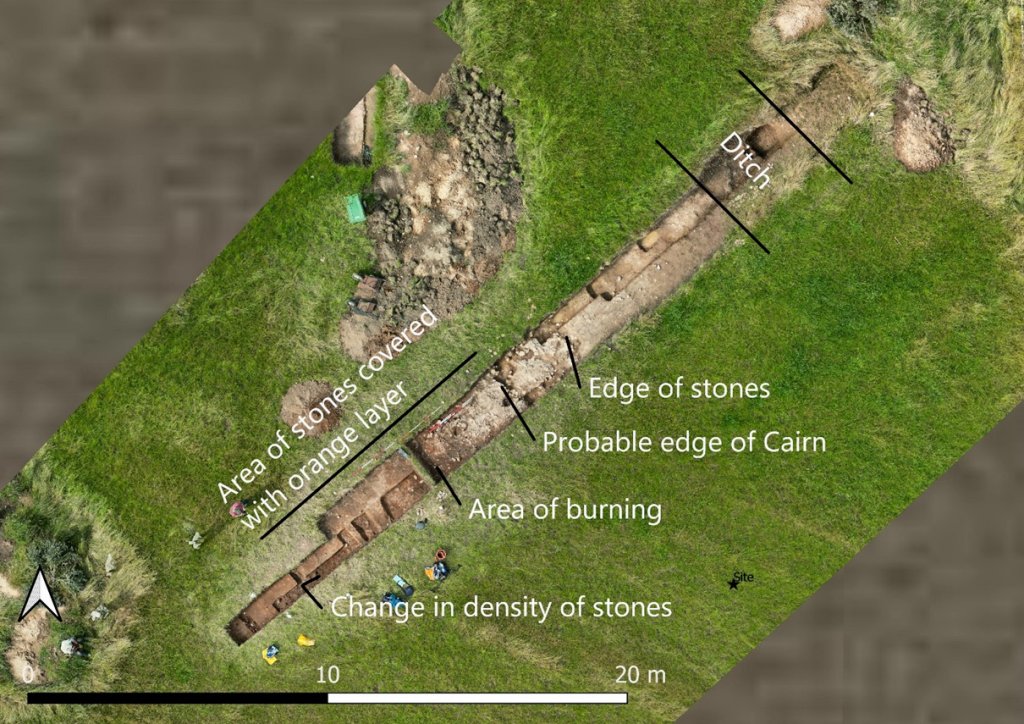

Interior. Work on the internal area of the ring ditch began in May 2023 by asking the farmer to use his machine to extend Trench 1 towards the centre (we chose Trench 1 as this had a more positive natural surface which we could use as a reference to define the nature of the mound). Showing great dexterity he delicately removed the topsoil and as he moved away from the ditch, the underlying subsoil could be seen giving way to soft, orange coloured, sandy clay. After about six metres, a well-defined stony layer appeared which we presumed to be the edge of a possible central cairn.  The stones, which lay on top of the soft sandy clay, seemed consistent with the bedrock material we had encountered in the ditch and therefore likely to have come from it. As we extended the trench (we were now calling Trench 1a) further towards the centre of the mound, large areas of burning were revealed overlying the stones. This was sealed beneath a layer of mottled sandy clay which was particularly thick in the central area. Banding in the clay suggested it could be the result of turfs. Small flints began appearing – mostly debitage but there was one identifiable thumb-scraper (likely to be Mesolithic but could also be Bronze Age). To add to our excitement, a small polished hand-axe appeared amongst the stone scatter. It was made of sandstone, a material unsuitable for use as a useable tool. Also its size suggested it was a ‘representative’ ceremonial deposit (similar examples have been found on Orkney).

The stones, which lay on top of the soft sandy clay, seemed consistent with the bedrock material we had encountered in the ditch and therefore likely to have come from it. As we extended the trench (we were now calling Trench 1a) further towards the centre of the mound, large areas of burning were revealed overlying the stones. This was sealed beneath a layer of mottled sandy clay which was particularly thick in the central area. Banding in the clay suggested it could be the result of turfs. Small flints began appearing – mostly debitage but there was one identifiable thumb-scraper (likely to be Mesolithic but could also be Bronze Age). To add to our excitement, a small polished hand-axe appeared amongst the stone scatter. It was made of sandstone, a material unsuitable for use as a useable tool. Also its size suggested it was a ‘representative’ ceremonial deposit (similar examples have been found on Orkney).

As we extended the trench further across the central area (Trench 1b), more areas of burning were showing up. This was represented by dark charcoal-rich patches and red stained stones. It was obvious that there had been a great deal of burning in the central area of the ring ditch.  The burning layer was represented in the section by a thin black line. It was also becoming apparent that this line was topped by a band of red sandy clay material, varying in thickness and colour from bright orange to crimsons.

The burning layer was represented in the section by a thin black line. It was also becoming apparent that this line was topped by a band of red sandy clay material, varying in thickness and colour from bright orange to crimsons.

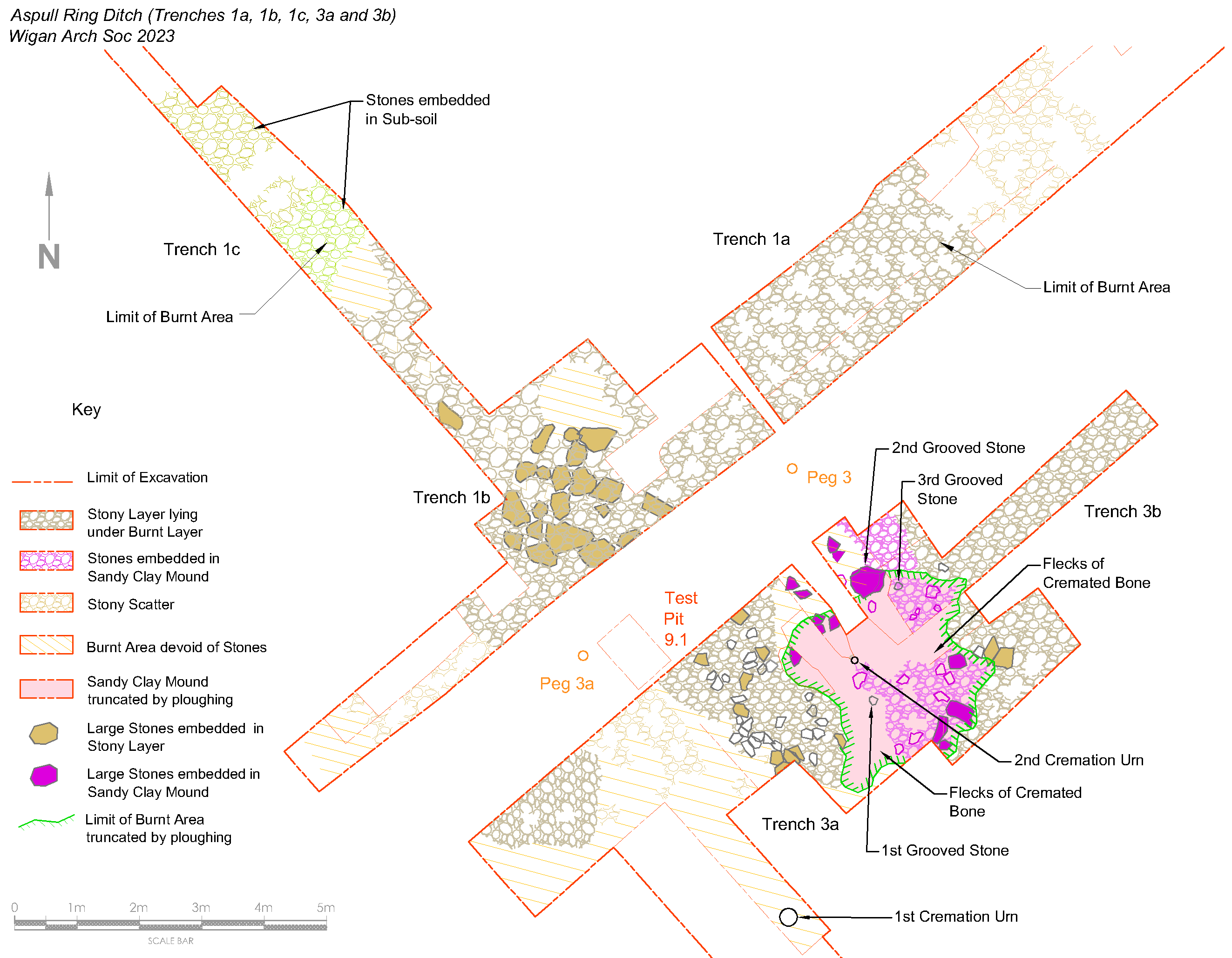

These layers were sandwiched between the stones and the overlaying mottled sandy clay layer. To determine how far this arrangement went away from the centre we asked the farmer to open another trench on the southeast side. He did this by extending Trench 3, removing the top soil all the way up as far as the new trenches in the centre but leaving a 2m baulk for access (this became Trench 3a). Working from the central area southeast- wards, the outer edge of the stony area was soon found, but seemed to be more ragged than the edge in Trench 1a. By expanding the trench on either side, more stones were revealed, but there were also areas of soft sandy clay devoid of stone lying under the burning and mottled clay layers.  It was while pursuing the extent of the burning layer in Trench 3a, away from the centre, that we came across our next most exciting find. Just below the topsoil, amongst a patch of burning, small pieces of cremated bone started appearing. Careful excavation revealed the rim of a pot just over 30cm in diameter.

It was while pursuing the extent of the burning layer in Trench 3a, away from the centre, that we came across our next most exciting find. Just below the topsoil, amongst a patch of burning, small pieces of cremated bone started appearing. Careful excavation revealed the rim of a pot just over 30cm in diameter.  Further investigations revealed it to be only the top part of a cremation urn, the rest being apparently destroyed by ploughing. This was not a wholly negative result, though, as it also told us that the covering mound must have been significantly higher in the Bronze Age. It was obvious the remains lay in a pit, cut into the mottled clay layer and seemed to be lying on top of the burning layer.

Further investigations revealed it to be only the top part of a cremation urn, the rest being apparently destroyed by ploughing. This was not a wholly negative result, though, as it also told us that the covering mound must have been significantly higher in the Bronze Age. It was obvious the remains lay in a pit, cut into the mottled clay layer and seemed to be lying on top of the burning layer.  As we were most likely dealing with human remains, we had to contact the local coroner which involved a day spent getting phone calls from puzzled police officers. This ended with a meeting on site by two officers and two small containers of cremated bones were ‘seized’ for possible forensic examination (a crime, they had to admit, they weren’t likely to solve). Removing anymore fragments of bone would require permission from the coroner and even a licence, so the remains were covered over to protect them from the weather (and Snowy our site dog). Further fragments of bone were turning up in areas on the northeast side of Trench 3a which were all treated in the same way. We now had positive evidence that we were dealing with the site of an large funerary monument and great care needed to be taken in our further excavations.

As we were most likely dealing with human remains, we had to contact the local coroner which involved a day spent getting phone calls from puzzled police officers. This ended with a meeting on site by two officers and two small containers of cremated bones were ‘seized’ for possible forensic examination (a crime, they had to admit, they weren’t likely to solve). Removing anymore fragments of bone would require permission from the coroner and even a licence, so the remains were covered over to protect them from the weather (and Snowy our site dog). Further fragments of bone were turning up in areas on the northeast side of Trench 3a which were all treated in the same way. We now had positive evidence that we were dealing with the site of an large funerary monument and great care needed to be taken in our further excavations.

Sandy Clay Mound A patch of sandy clay, also on the northeast side of Trench 3a, appeared to be different than the other areas of sandy clay devoid of stone. Cutting a sondage (S5) into it, seemed to show that the overlaying burning and mottled clay layers had been sheared off the top of what appeared to be a rising mound of sandy clay.  It was while investigating this Sandy Clay Mound that our next exciting discovery turned up. This was another ceramic pot, buried upside in the mound (significantly buried, not in a cut in the mound). It was much smaller than the the previous find but, a part from a large crack, seemed complete.

It was while investigating this Sandy Clay Mound that our next exciting discovery turned up. This was another ceramic pot, buried upside in the mound (significantly buried, not in a cut in the mound). It was much smaller than the the previous find but, a part from a large crack, seemed complete.  Closer inspection revealed an incised criss-cross pattern on its surface. Its size and location, suggested a much earlier phase in the life of the monument.

Closer inspection revealed an incised criss-cross pattern on its surface. Its size and location, suggested a much earlier phase in the life of the monument.

Although no bones were found associated with it, we realised this would again need care handling so, until we could arrange for its careful removal, examination and storage, we decided to leave it in situ, covering it over as before to protected from the elements (contact with Ian Miller at GMAAS produced a kind offer of a place at the Salford University Labs for its study).

Expanding Trench 3a further in the northeast direction produced one more important find – a sherd of pottery embedded in the stony layer. The criss-cross pattern on its surface indicated it was clearly from another Bronze Age urn. This time the pattern had not been incised but impressed perhaps by thin cord or serrated wheel which suggests a later date.  This isolated sherd also indicated there was another cremation somewhere but further extension of Trench 3a failed to find any. This, together with our other finds, did show however that our site had been in use over a long period of time.

This isolated sherd also indicated there was another cremation somewhere but further extension of Trench 3a failed to find any. This, together with our other finds, did show however that our site had been in use over a long period of time.

To investigate the full extent of the stony and burning layers, Trench 1b was extended in the northwest direction towards Trench 5 in the northwest quadrant (producing Trench 1c). Here the extent of these layers could be seen but surprisingly they seem to be diving under a new layer of stones embedded in the subsoil which had started to appear.  By the time we reached Trench 5, this new stony layer had disappeared leaving just a soft sandy clay lying under a thick layer of subsoil. This is what we had discovered the previous year when Trench 5 was excavated. It wasn’t clear at the time what was happening to the natural ground surface we had established around the edges of the ditch. This consisted of a hard compacted clay embedded with small pebbles (a typical glacial till). However this seemed to quickly disappear after just a couple of metres away from the ditch to be replaced by the soft sandy clay, eventually being topped by the thick layer of subsoil. The point where the compacted clay layer disappeared and the soft sandy clay appeared, was marked by a small outcrop of bedrock.

By the time we reached Trench 5, this new stony layer had disappeared leaving just a soft sandy clay lying under a thick layer of subsoil. This is what we had discovered the previous year when Trench 5 was excavated. It wasn’t clear at the time what was happening to the natural ground surface we had established around the edges of the ditch. This consisted of a hard compacted clay embedded with small pebbles (a typical glacial till). However this seemed to quickly disappear after just a couple of metres away from the ditch to be replaced by the soft sandy clay, eventually being topped by the thick layer of subsoil. The point where the compacted clay layer disappeared and the soft sandy clay appeared, was marked by a small outcrop of bedrock.  When the area between this and the end of the trench was further excavated (now referred to as Trench 5b), we were able to establish a hard compacted clay layer laying under the soft sandy clay. However the issue about whether this soft sandy clay layer was manmade or a natural deposit, had still not been resolved, despite it appearing to be spread all across the whole internal area of the ring ditch. It was hard to imagine it being natural but, if was manmade, where did the material come from and why was there little or no evidence of its deposit in the form of banding (similar to the sections seen in the mottled clay layer).

When the area between this and the end of the trench was further excavated (now referred to as Trench 5b), we were able to establish a hard compacted clay layer laying under the soft sandy clay. However the issue about whether this soft sandy clay layer was manmade or a natural deposit, had still not been resolved, despite it appearing to be spread all across the whole internal area of the ring ditch. It was hard to imagine it being natural but, if was manmade, where did the material come from and why was there little or no evidence of its deposit in the form of banding (similar to the sections seen in the mottled clay layer).

We also opened a cut on the northeast side of Trench 3a (Trench 3b) to see if we could establish the extent of the stony layer in that direction. Even after 4m however the stony and burnt layers were still evident. The possible projected area of these layers therefore could only be guessed at.

In the main area of Trench 1b, larger stones where poking through the small stones in the stony layer. To investigate the extent of these stones, the stony layer was cut through down to the underlying soft sandy clay. This revealed a substantial area of large, mainly flat, stones.  There was no obvious pattern to their distribution – a causeway didn’t seem plausible as, although embedded in the stony layer, most were lying below the upper surface of the stony layer.

There was no obvious pattern to their distribution – a causeway didn’t seem plausible as, although embedded in the stony layer, most were lying below the upper surface of the stony layer.

Further investigation of the Sandy Clay Mound in Trench 3a revealed it to be covered on its southwest with the stony layer. However on the opposite side, a layer of stones seem to be embedded in the mound.

Grooved Stones. Some of the stones embedded in the Sandy Clay Mound were quite large. The largest of these stones produced our final and most unusual find of the season. Inscribed on the lowest section of the block were a series of parallel lines. These were not the usual random spirals or cup marks you get in the Neolithic but quite straight and evenly cut lines.  As far as we can tell, this is totally unprecedented for this period. A much smaller stone with similar grooves had already been spotted in the stony layer but, at the time, had been dismissed as a possible intrusion. When yet another small stone with with similar but more pronounced grooves appeared in the small stones embedded near the surface of the mound, we realise we had discovered something very peculiar (at the time of writing we not been able to find anything comparable).

As far as we can tell, this is totally unprecedented for this period. A much smaller stone with similar grooves had already been spotted in the stony layer but, at the time, had been dismissed as a possible intrusion. When yet another small stone with with similar but more pronounced grooves appeared in the small stones embedded near the surface of the mound, we realise we had discovered something very peculiar (at the time of writing we not been able to find anything comparable).

Thus ended our second digging season – a season that has seen lots of interest from archaeological groups from across the region. Many have volunteered their services, including groups from the Wyre, Liverpool and even Cheshire. We also have had a session from Manchester’s Young Archaeologists Club who thoroughly enjoyed their day with us.

Thus ended our second digging season – a season that has seen lots of interest from archaeological groups from across the region. Many have volunteered their services, including groups from the Wyre, Liverpool and even Cheshire. We also have had a session from Manchester’s Young Archaeologists Club who thoroughly enjoyed their day with us.

As usual you can find out our detailed progress this season our Site Diary here

C14 Dating (Season2). During the year, we took a sample of charcoal from inside our first urn and from a large patch in the central area of Trench 3a. Both were duly sent off for analysis at Queens University (grant from CBA NW applied for). Results came back within a couple of months, this time giving an early Bronze Age date (i.e. 1900 (95.4%) 1740 cal BC). Notably both samples were within the same date range, suggests that the burning event, the cremation and the creation of the mottled clay mound, all occurred within 160 years of each other. We do however perhaps have an earlier phase represented by the Sandy Clay Mound which has our second urn in it (and possibly an even earlier phase if we consider the ring ditch to be a Neolithic henge).

Fossil Stones (Season3). One of the most mysterious finds from our excavations last year was a collection of Grooved Stones – a very large one(over half a metre) and two small ones (just over 10cms). Another very small one (not much more than 5cms) has also been found this year.

At the time we had no idea what to make of these as we were unable to find anything like them in any other Bronze Age or Neolithic context. However a close study of one of the small ones in the low afternoon sunlight, has revealed small cells running along the tops of the ridges. These are very similar to tree-like club moss fossil occurring in the Carboniferous period known a Sigillaria.  The general consensus now is that all these stones are in fact fossils. Appearing as they do in close proximity to the central Sandy Clay Mound, suggests they have had some significance to the ancient builders of the monument.

The general consensus now is that all these stones are in fact fossils. Appearing as they do in close proximity to the central Sandy Clay Mound, suggests they have had some significance to the ancient builders of the monument.

We are still finding small flints, some of which could well be tools. Two of these could easily be used to punch holes in leather. Another enigmatic find from last year was small, well-formed stone ball. It was unfortunately found on the spoil heap but analysis of our daily drone images strongly suggests that it must have come from archaeological layers around our Sandy Clay Mound. It seems to be made of something like hard granite and is quite heavy for its size.

It has been dismissed as a cannon ball as it isn’t round enough, shaped more like a tangerine. It could though, possibly be a sling shot used for bring down large game (although a lot of work for a single-use throw away item). Another suggestion is that it’s a coal ball, a natural forming feature found in coal measures although it doesn’t seem to be the right material. Maybe it’s one of the stone balls that are found in their hundreds in Scotland. Most of them are elaborately carved but some are plain and some have been found in Neolithic contexts. However very few have been found south of the border and these in Northumbria. Another possible explanation is that it is in fact another fossil i.e. a concretion around something like an ammonite

Coring Survey (Season3). A combination of good weather in February and the availability of Chris Drabble’s Border Heritage Archaeology Group (BHAG) from Cheshire, provided us with an opportunity for a pre-season site visit to do more coring. We had always planned to do the East Quadrant of the ring ditch, following on from last year’s coring exercise in the South Quadrant. The result seem to show that, as in the other Quadrant, the the ditch was continuous (i.e. no sign of an entrance) and more or less where we had predicted the ditch to be. Although also as before, there were a couple of areas were there may be an interruption in the ditch similar to Trench 5 / 5a (only excavation would prove this).

Excavations (Season3) (Return to Index)

The unusually clement February weather gave Chris Drabble and his team from BHAG an opportunity to do some pre-season trowelling on a section in the central area. The section selected was close to our first cremation urn where the plough soil had been removed but still had a layer of soil on it. It was a fairly simple task that wasn’t expected to reveal any surprises. However, as the underlying mottled sandy clay began to be revealed, a strange pattern emerged, octagonal in shape and defined by a thin band of bright orange clay. Significantly it’s internal area seemed to containing organic or burnt material.  It was still too early in the season to allow for any meaningful investigate, so it was covered up and left for us to work on later in the year.

It was still too early in the season to allow for any meaningful investigate, so it was covered up and left for us to work on later in the year.

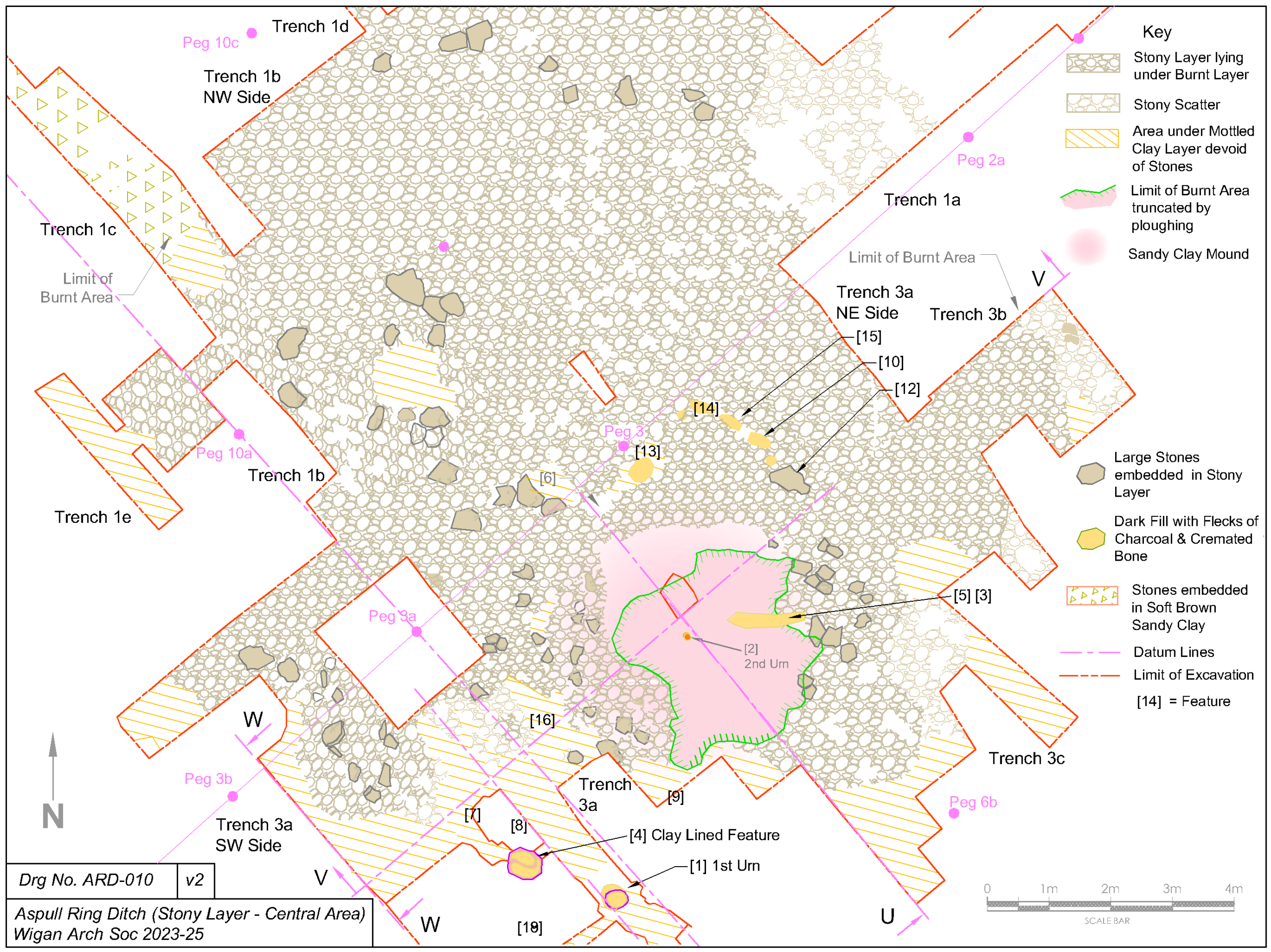

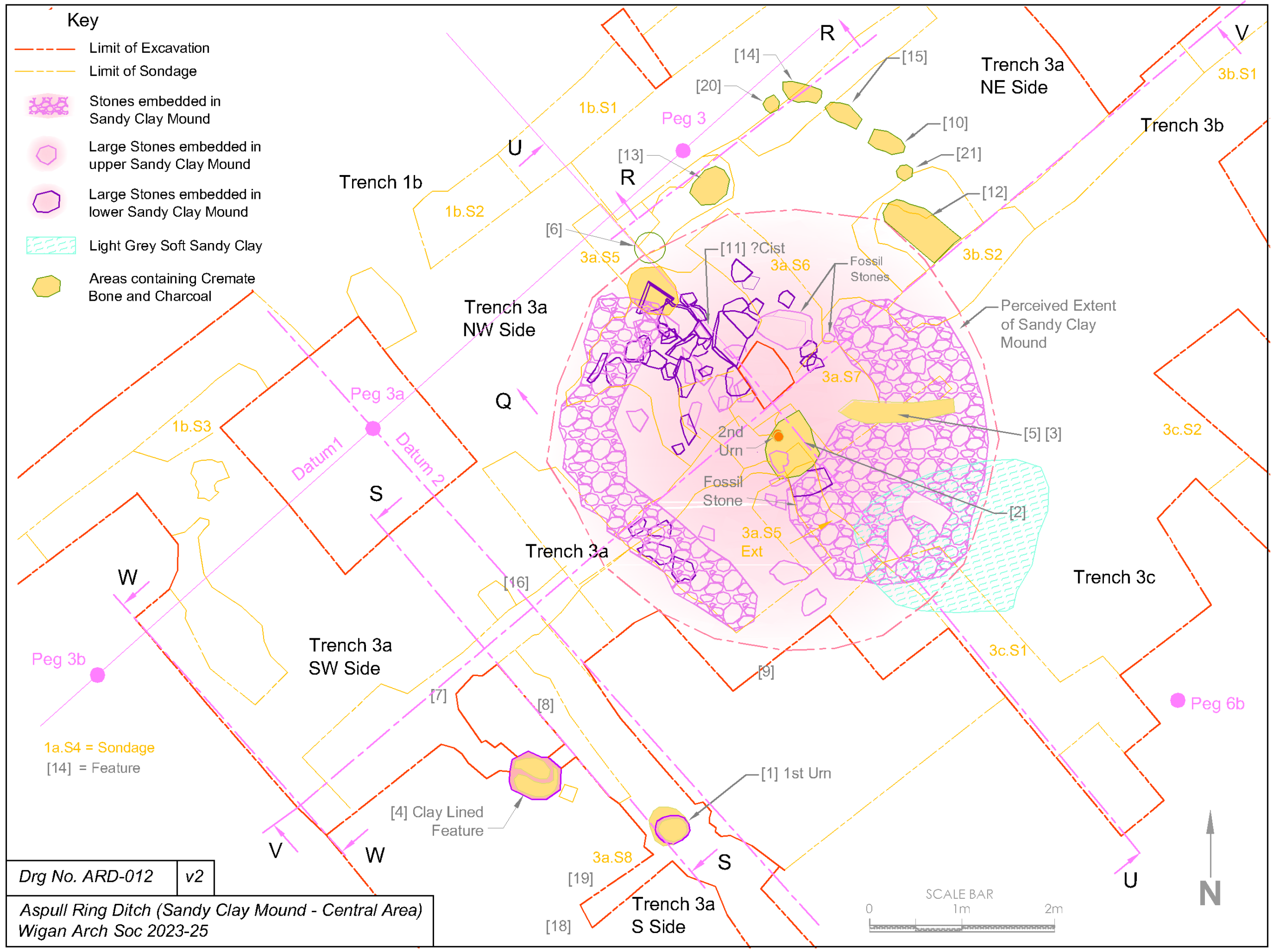

Trench 1b to 3a. Excavations started in earnest in April and the first task was to continue with investigation the collection of large flat stones discovered towards the end of last year in Trench 1b. Their arrangement seemed to suggest a heading in the general direction of the central Sandy Clay Mound in Trench 3a. Trench 1b was therefore extended in that direction and sure enough more large stones emerged.  The trench was therefore widened and extended until it eventually broke through into Trench 3a. This however did not reveal more large stones but the spread of smaller stones did continue and seemed to be getting thicker. Circular patterns seemed to be emerging in them but further work to remove the smaller stones around these patterns revealed no significant feature. There were however pockets devoid of stone, one in particular circling around the central Sandy Clay Mound. This pocket, when investigated, seemed to connect to other pockets surrounding the central Sandy Clay Mound.

The trench was therefore widened and extended until it eventually broke through into Trench 3a. This however did not reveal more large stones but the spread of smaller stones did continue and seemed to be getting thicker. Circular patterns seemed to be emerging in them but further work to remove the smaller stones around these patterns revealed no significant feature. There were however pockets devoid of stone, one in particular circling around the central Sandy Clay Mound. This pocket, when investigated, seemed to connect to other pockets surrounding the central Sandy Clay Mound.  Further work in this area also revealed a fair depth of stones surrounding the central Sandy Clay Mound, which seemed to be acting as a revetment (but only on its west flank). The ‘revetment’ became a jumble of larger stones in the area around the northwest side of Sondage S5 (near where we could see the truncation of the Sandy Clay Mound). Some of the stones were thin slabs and, excitingly, a few seemed to be in a semi-vertical position.

Further work in this area also revealed a fair depth of stones surrounding the central Sandy Clay Mound, which seemed to be acting as a revetment (but only on its west flank). The ‘revetment’ became a jumble of larger stones in the area around the northwest side of Sondage S5 (near where we could see the truncation of the Sandy Clay Mound). Some of the stones were thin slabs and, excitingly, a few seemed to be in a semi-vertical position.  Also in the section wall, there appeared to be a dip in the mottled clay and burnt layers. Quite close to this, a pocket of darker sandy clay extended under the stones which revealed some more cremated bone. This was obviously going to be an area of particular interest – we therefore decided to leave it for the time being for investigation later in the season.

Also in the section wall, there appeared to be a dip in the mottled clay and burnt layers. Quite close to this, a pocket of darker sandy clay extended under the stones which revealed some more cremated bone. This was obviously going to be an area of particular interest – we therefore decided to leave it for the time being for investigation later in the season.

Trenches 3b and 3c. One of the aspects of the central area that we hadn’t been able to resolve last year, was the extent of the mottled, burnt and mottled clay layers on its east side. We therefore expanded Trench 3b in an north-easterly direction until the stony layer ran out into just a scatter. However the mottle clay and some evidence of burning seemed to continue.

To extend Trench 3a in the southeast, it was evident we need to push back the spoil heap. A few attempts were made by hand but these hadn’t made much impression, so Nick the farmer was called. His machine made light work of it, not only removing the spoil heap but removing the topsoil over a good few metres to the southeast. Trenches (S1 and S2) down either side of the newly exposed area (now labelled 3c), quickly revealed the extent of the stony layer in this area.  Trowelling the rest of the area revealed the extent of the stony layer but, as in the other areas, did not produce a clean edge, just seeming to peter out into a scatter of stones.

Trowelling the rest of the area revealed the extent of the stony layer but, as in the other areas, did not produce a clean edge, just seeming to peter out into a scatter of stones.  Trench 3b therefore was widened so that the edge of the stony layer could be followed on the northeast side of Trench 3c. This revealed more of the ragged edge to the stony layer and a cut towards the southeast eventually revealed the limit of it in that direction.

Trench 3b therefore was widened so that the edge of the stony layer could be followed on the northeast side of Trench 3c. This revealed more of the ragged edge to the stony layer and a cut towards the southeast eventually revealed the limit of it in that direction.

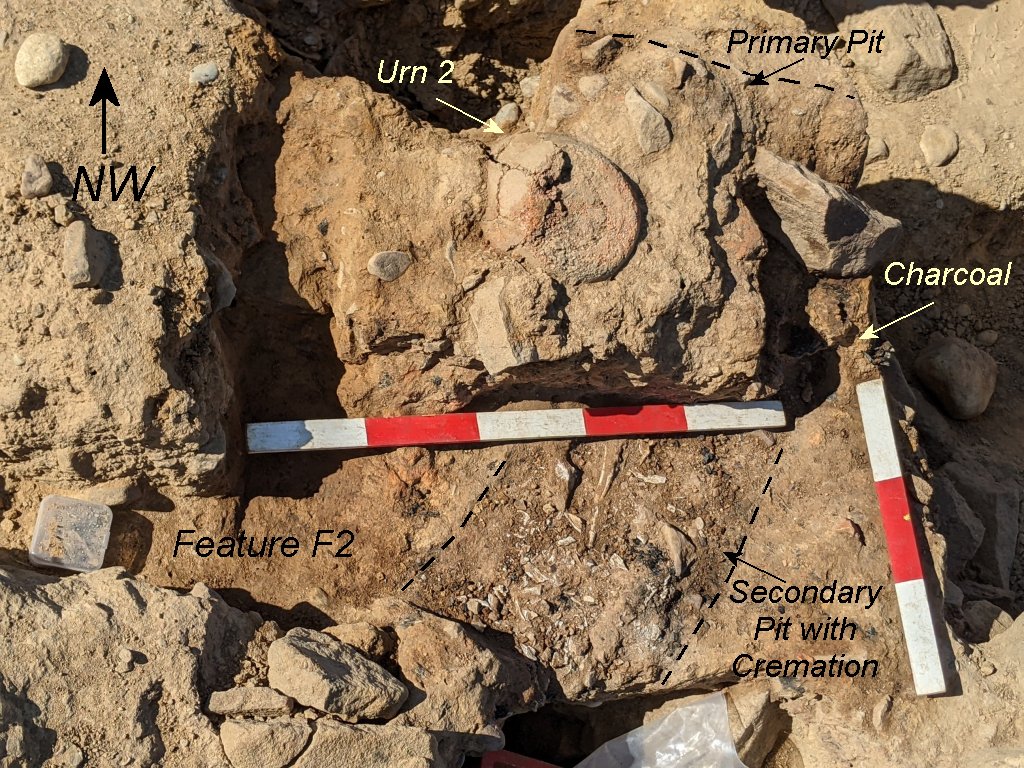

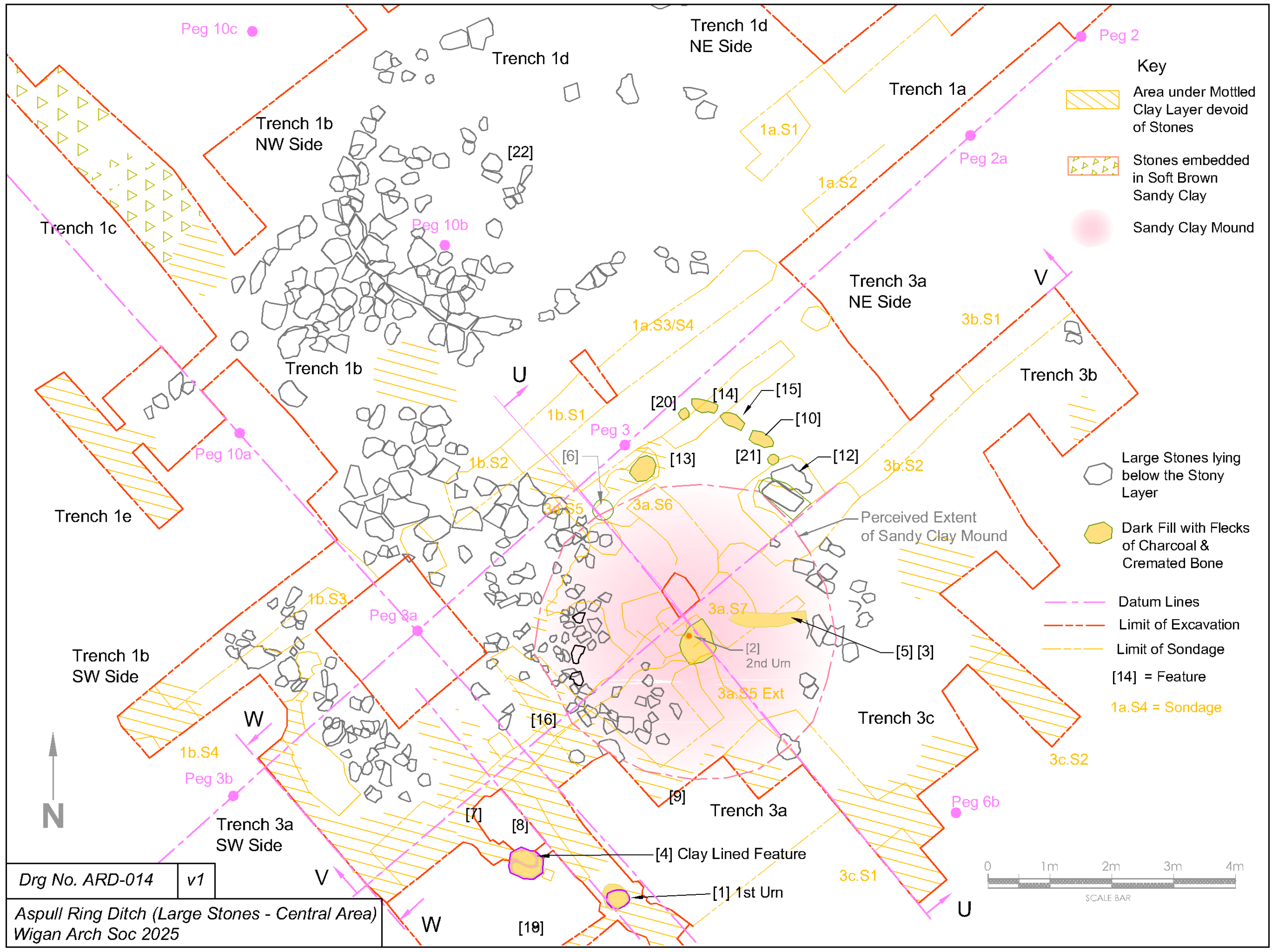

Central Area Sections. We now had a general idea of the extent of the stony layer in all directions (but still not the burning or mottled clay layers). As well as recording the plan of the central area, we also needed to record sections through it. Two sections were chosen which would hopefully capture the Sandy Clay Mound and its association with the surrounding stony, burnt and mottled clay layers. These lines fortunately already had the sections exposed in the side walls of the trenches in some areas. However other areas needed to be developed. One in particular was the area southeast of our second urn ( labelled Sondage S5 Ext). This revealed quite a depth of stone on the east flank of the Sandy Clay Mound (at the time thought possibly a separate cairn). At depth a large stone block emerged and above it just to the south east of our second urn a brown fill produced a quantity of charcoal and cremated bone.

The section line running at ninety degrees to this was also developed by joining the sondage with the fossil stone in it (S6) and Sondage S5 on the northeast side of our second urn. This revealed quite a depth of soft sandy clay with just a smattering of stones embedded in it.

It was decided to open up a sondage to the southeast of this cut on the northeast side of our second urn (labelled S7). This was to establish how far the Sandy Clay Mound extended before encountering the embedded stones this side of the mound. After about a metre the full depth of embedded stones was revealed corresponding with the previously revealed cairn-like feature seen in sondage S5 Extension.  In the Sandy Clay Mound, colouration and banding was noticed for the first time which gave more credence it’s manmade construction.

In the Sandy Clay Mound, colouration and banding was noticed for the first time which gave more credence it’s manmade construction.

As this sondage was extended towards our second urn, it was noticed that the brown fill seen in S5 Extension, appeared on this side as well. It was in a pit cut into the Sandy Clay Mound with a well defined flat bottom.  When the area around the vessel itself was examined more closely, the brown fill could be seen down the side of it which means that the urn was actually in the pit as well. This was contrary to our previous assumption, in that the vessel had been buried with the Sandy Clay Mound, as no pit could be detected at the time. It also means that the Sandy Clay Mound cannot be dated from the contents of the urn (except that it must be older than the contents of the pit).

When the area around the vessel itself was examined more closely, the brown fill could be seen down the side of it which means that the urn was actually in the pit as well. This was contrary to our previous assumption, in that the vessel had been buried with the Sandy Clay Mound, as no pit could be detected at the time. It also means that the Sandy Clay Mound cannot be dated from the contents of the urn (except that it must be older than the contents of the pit).

First Cremation Urn. During the year we had a visit from Ben Dyson from Greater Manchester Archaeological Advisory Service, who was able to give us great advise on how to deal with the burials we were discovering. Although not being able to help us with the octagonal feature burial, he did say he would supervise the removal of the other two urns we discovered last year. He also made a point in say he was very happy with our work and was confident the site was in good hands.

Before Ben came on site, we took the opportunity to clean up our first urn which had suffered from moss growth due to the warm and wet conditions. In doing so, soil fell away from the side of the vessel revealing more of the vessel’s side. This showed that it was not upside down, as we had previously concluded, but the right way up.

This was great news as we realised the urn had retained most of its contents of charcoal and cremated bone. At the beginning of the year, in anticipation of receiving removal permission, a fragment of cremated bone had been sent off to CARD for dating with their programme. When the result came back, it revealed a date of between 1891 and 1688 (95.4 %) cal. BC – very similar to the dates we had obtained last year for the charcoal from this feature and also the burnt layer covering the stones near the central Sandy Clay Mound.

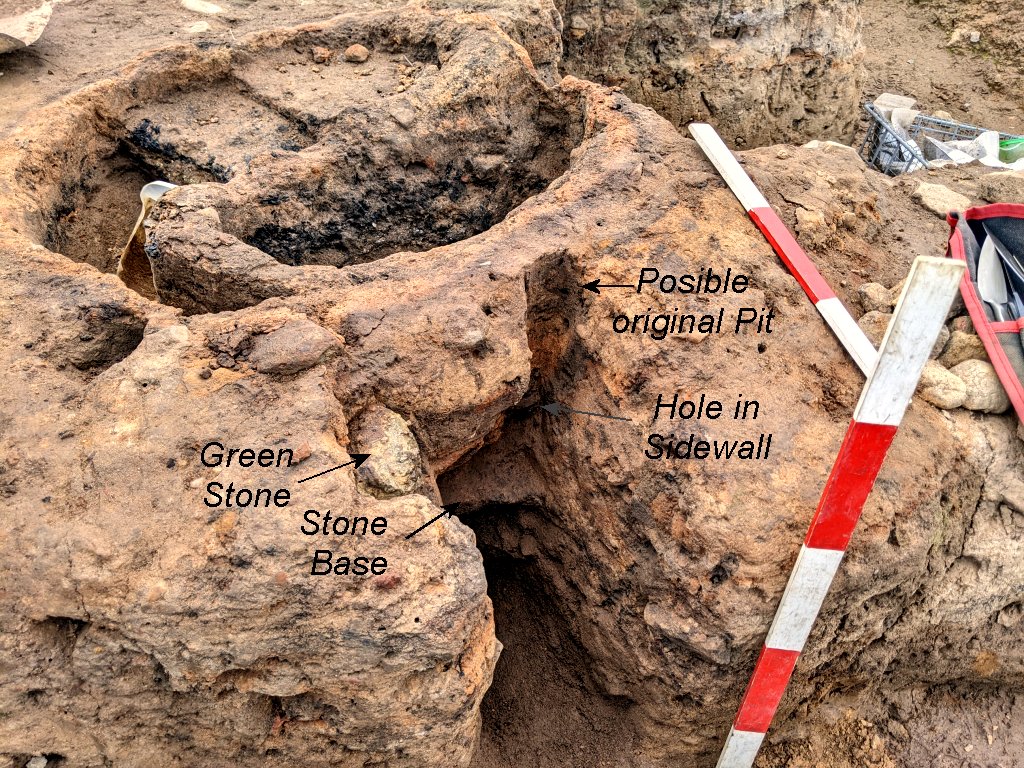

Octagonal Feature. Although the octagonal feature had been discovered early on in the season it wasn’t until the end of April before work started on it in earnest. Once investigations commenced though, they continued on it throughout the year. It was a few weeks in before the first signs of cremated bone began to appear but it was many weeks later before true nature of the feature became clear (although still not fully understood).  What we seem to have is another burial as it contained large quantities of cremated bone in layers interspersed with layers of burnt wood (a possible interpretation is that it’s a family plot). It also seems to have a strange internal partition and possibly a stone base.

What we seem to have is another burial as it contained large quantities of cremated bone in layers interspersed with layers of burnt wood (a possible interpretation is that it’s a family plot). It also seems to have a strange internal partition and possibly a stone base. The bright orange clay defining the feature, was at first though to be a poorly fired vessel. However, excavating down the side of it revealed no sign of a pit in which was placed. Our thoughts now are that it is more likely to be a clay lined pit.

The bright orange clay defining the feature, was at first though to be a poorly fired vessel. However, excavating down the side of it revealed no sign of a pit in which was placed. Our thoughts now are that it is more likely to be a clay lined pit.  We haven’t as yet come across anything remotely comparable.

We haven’t as yet come across anything remotely comparable.

Feature F6. As the season progressed we started to look at the strange dip in the mottled clay we’d seen earlier in the year, in the section wall just to the northwest of Sondage S5. It seemed to be associated with a cut in the underlying sandy clay (which was labelled F6).  A half section was cut through it which revealed it to conical in shape and very localised. However as we expanded the cut further to the northeast other features seem to emerge, perhaps a vee shaped cut and groups of stones above and below the burnt layer and gaps devoid of stone.

A half section was cut through it which revealed it to conical in shape and very localised. However as we expanded the cut further to the northeast other features seem to emerge, perhaps a vee shaped cut and groups of stones above and below the burnt layer and gaps devoid of stone.  It was quite confusing so the cut was widened and extended and another sondage from the main area of Trench 3a was cut through to join it. To our relief the usual arrangement of the burnt layer lying on top of the stony layer was established but still leaving the odd patch devoid of stones.

It was quite confusing so the cut was widened and extended and another sondage from the main area of Trench 3a was cut through to join it. To our relief the usual arrangement of the burnt layer lying on top of the stony layer was established but still leaving the odd patch devoid of stones.

Possible Cist. It was about this time that we made an exciting discovery. The small cavity first detected in side wall of Sondages S5, we found to be connected to a much larger one going right under the baulk between S5 and S6 (the sondage containing the large fossil stone). It happened to be close to where we had come across the large thin slabs, so we were quite excited about what this could mean (we tried to get a photo of the inside but this didn’t reveal much).  It was decided therefore to take down the baulk to investigated it further. As we removed the topsoil however some other features emerged including a thin row of small stones embedded in the Sandy Clay Mound in an area otherwise devoid of stones (it was unfortunate we hadn’t see these when the sondages where dug on either side).

It was decided therefore to take down the baulk to investigated it further. As we removed the topsoil however some other features emerged including a thin row of small stones embedded in the Sandy Clay Mound in an area otherwise devoid of stones (it was unfortunate we hadn’t see these when the sondages where dug on either side).  As we worked down closer to the cavity a sheet was placed in it in an attempt to protect any material inside from contamination from upper levels. Once all the overlying soft sandy clay had been removed a large thin-ish slab emerged partially protecting the cavity but it had been broken in two presumably due to the weight of the overburden. The cavity project beyond this slab however, seemingly protected by a grouping of embedded stones (but strangely not completely).

As we worked down closer to the cavity a sheet was placed in it in an attempt to protect any material inside from contamination from upper levels. Once all the overlying soft sandy clay had been removed a large thin-ish slab emerged partially protecting the cavity but it had been broken in two presumably due to the weight of the overburden. The cavity project beyond this slab however, seemingly protected by a grouping of embedded stones (but strangely not completely). This was a disappointment – if it had been the main burial (in the form of a cist), it had been very badly damaged and therefore the prospect of finding and evidence of its occupant much reduced. All the same, it was decided to leave its investigation till we had more time to deal with any possible remains.

This was a disappointment – if it had been the main burial (in the form of a cist), it had been very badly damaged and therefore the prospect of finding and evidence of its occupant much reduced. All the same, it was decided to leave its investigation till we had more time to deal with any possible remains.

Trench 3a NE Side. Work continued however in Trench3a extending Sondage S6 and also expanding the trench on the northeast side to explore the patches devoid of stone we had previously seen. In one of the patches some flecks of cremated we detected. As this was the first time we were getting cremated bone on this side of the central Sandy Clay Mound, it was decided to open up the is whole area to check the for more possible cremations.  The trench was eventually pushed back a further two metres and trowelled down to the mottled clay layer. This revealed some darker brown patches in the clay.

The trench was eventually pushed back a further two metres and trowelled down to the mottled clay layer. This revealed some darker brown patches in the clay.  When one of these was investigated (F10), it turned out to have more flecks of cremated bone in a pocket going through the underlying burnt and stony layers. The whole area was therefore treated with some care.

When one of these was investigated (F10), it turned out to have more flecks of cremated bone in a pocket going through the underlying burnt and stony layers. The whole area was therefore treated with some care.  Trowelling away the mottled clay on the southeast side of the area (near the section coming across from Trench 3b) revealed two large stone slabs (F12) in the underlying stony layer. As they were close to the section already dug, it was easy to look beneath them which revealed another cavity. Excitingly this also had cremated bone in it.

Trowelling away the mottled clay on the southeast side of the area (near the section coming across from Trench 3b) revealed two large stone slabs (F12) in the underlying stony layer. As they were close to the section already dug, it was easy to look beneath them which revealed another cavity. Excitingly this also had cremated bone in it.  When the stone slabs were removed a large pit was revealed containing small stones. As is good practice, the pit was half sectioned revealing at the bottom, a large cache of charcoal and cremated bone.

When the stone slabs were removed a large pit was revealed containing small stones. As is good practice, the pit was half sectioned revealing at the bottom, a large cache of charcoal and cremated bone.  Some of the pieces were quite large (a possible vertebrae even). A sample was selected for dating with CARD as this feature lies securely below the burnt layer and therefore must be old than our previous dates.

Some of the pieces were quite large (a possible vertebrae even). A sample was selected for dating with CARD as this feature lies securely below the burnt layer and therefore must be old than our previous dates.

As the rest of the area was trowelled through the burnt layer to the stony layer, more flecks of cremated bone began to turn up in pockets of darker sandy clay. One of these on the northwest edge of the trench was producing more and more as the pocket got deeper. Opening up the area, the pocket turned out to be a pit and in the bottom was another collection of charcoal and cremated bone.  Again this burial had some large pieces, perhaps skull fragments.

Again this burial had some large pieces, perhaps skull fragments.

We now had three more confirmed cremation burials to add to the two we had found the previous year (and we still had the possible cist to investigate). However strange as it may seem, each burial is different in one way or another which suggest the site was in use over a long period (more carbon dating will hopefully give us the definitive answer).

Trench 3a SW Side. On the southwest side of Trench 3a there was an area of the stony layer which seemed to be isolated from the rest and its apparent circular appearance suggested perhaps a separate cairn.  Further work on the stones showed they had a some depth so it was decided to expand the trench in the northwest direction. A section down the southwest side would also perhaps reveal how deep the stones went. The first extension towards Trench 1b revealed a large area of burning lying under the mottled clay layer. This at first seemed to be a feature in itself as it was higher than expected in the mottled clay layer.

Further work on the stones showed they had a some depth so it was decided to expand the trench in the northwest direction. A section down the southwest side would also perhaps reveal how deep the stones went. The first extension towards Trench 1b revealed a large area of burning lying under the mottled clay layer. This at first seemed to be a feature in itself as it was higher than expected in the mottled clay layer.  When mottled clay layer was removed and the underlying stony layer exposed, no feature emerged. Also the section down the southwest side showed the depth of the stony layer to be limited and resting on a band of brown soft sandy clay, then the usual soft sandy clay.

When mottled clay layer was removed and the underlying stony layer exposed, no feature emerged. Also the section down the southwest side showed the depth of the stony layer to be limited and resting on a band of brown soft sandy clay, then the usual soft sandy clay.  The stony layer however did seemed to be continuing in a circle so cut was therefore extended further towards Trench 1b. This showed however the stony layer returning (perhaps around a small stake hole) to match the stony layer previously uncovered in Trench 1b.

The stony layer however did seemed to be continuing in a circle so cut was therefore extended further towards Trench 1b. This showed however the stony layer returning (perhaps around a small stake hole) to match the stony layer previously uncovered in Trench 1b.  This was confirmed when the cut was eventually extended all the way into Trench 1b.

This was confirmed when the cut was eventually extended all the way into Trench 1b.  The sections revealed in the mottled clay layer however where producing a complex of layering which may explain the higher level of burning we experienced. The band was at a shallow angle building from the southeast to the northwest.

The sections revealed in the mottled clay layer however where producing a complex of layering which may explain the higher level of burning we experienced. The band was at a shallow angle building from the southeast to the northwest.  This was in contrast to the layering in the section seen around the corner in trench 3a where the banding in the mottled clay layer is at a steep angle. We’ve always assumed this to be the result of turf lain upside down but this isn’t as obvious in the newly revealed section.

This was in contrast to the layering in the section seen around the corner in trench 3a where the banding in the mottled clay layer is at a steep angle. We’ve always assumed this to be the result of turf lain upside down but this isn’t as obvious in the newly revealed section.

Although there was no specific feature in the mottled clay layer, there seemed to be a circular pattern in one part of the stony layer where there was a particularly large stone. This was investigated by the careful removal of the stones after recording which showed some depth to the stony layer in this area.  Again though this produced no particular feature but the underlying soft sandy clay seemed to go quite deep – much deeper that the perceived depth in the adjacent sondages. This was particularly true in the cut down the southwest side which had revealed a rising natural ground surface.

Again though this produced no particular feature but the underlying soft sandy clay seemed to go quite deep – much deeper that the perceived depth in the adjacent sondages. This was particularly true in the cut down the southwest side which had revealed a rising natural ground surface.

Also on this southwest side of Trench 3a, a cut was extended across the southeast edge to enable the section drawing along this line to be completed. This also revealed an undulating natural ground surface, although as has been generally the case in all areas, it was difficult determining the exact level of the original surface. Typically the soft sandy clay lying above the harder stonier ground only contained small flecks indicating it being manmade.  However a dip in the harder surface developed into a pit and a large piece of charcoal fell out of it. This is interesting as it could provide a date for the construction of this phase of the mound.

However a dip in the harder surface developed into a pit and a large piece of charcoal fell out of it. This is interesting as it could provide a date for the construction of this phase of the mound.

Drawings (Season 3).

Central Area Plan (Stony Layer)

Central Area Plan (Sandy Clay Mound Layer)

Central Area Sections

Ring Ditch Work. During the year we had enough resource to continue our investigations of the Ring Ditch itself. We have been fortunate enough to be able to leave our ditch trenches open since they were first dug in 2022. The porous bedrock has meant that they generally remained dry. We’ve only back filled Trench 4 which had suffered a collapse. Trench 6 / 6a is the only one that regularly filled with water and had also suffered a major collapse.

Trench 1. This is the only other trench to suffer a collapse. It was therefore decided to clear the ditch so that site visitors could get a better understanding of the nature of our Ring Ditch. As the trench got wider however, an issue arose as to its direction of travel, as it seemed to be heading away from the predicted line of the ditch.  A new trench (Trench 1d) was therefore cut a couple of metres away on the northwest side. This eventually showed the ditch was going in the right direction. Further work on Trench 1 revealed that localised collapses of the fragile bedrock was probably the the reason for the perceived diversion from the predicted line.

A new trench (Trench 1d) was therefore cut a couple of metres away on the northwest side. This eventually showed the ditch was going in the right direction. Further work on Trench 1 revealed that localised collapses of the fragile bedrock was probably the the reason for the perceived diversion from the predicted line.

Trench 3d. Volunteers from the Border Heritage Archaeology Group from Cheshire were given the task at investigating the anomalous feature on the outer edge of Trench 3. When this was first discovered it appeared to be another ditch cut into the bedrock. However, as its fill of stone rubble was completely different from the usual ditch fill of soft brown sandy clay, the was some doubt about its origin. Could it be a natural feature. The shape edge of bedrock on its southeast side looked particularly manmade but what tools did the ancients have to produce such a clean edge. Also the rubble fill seemed to be going under the undisturbed bedrock.  As the trench was widened the sharp edge seemed to develop a curve but was terminated with more bedrock. The surface beyond the ditch, when cleaned revealed more apparent disturbed ground but, with no finds whatsoever, the origin of this feature is still unresolved.

As the trench was widened the sharp edge seemed to develop a curve but was terminated with more bedrock. The surface beyond the ditch, when cleaned revealed more apparent disturbed ground but, with no finds whatsoever, the origin of this feature is still unresolved.

Trench 6 / 6a. Although this trench had regularly looked like a swimming pool, a spell of dry weather had allowed it to drain. It was a shame to see it in such a state as when it was finished last year it had revealed a large smooth flat bedrock floor. Also the relationship between the two trenches had not been fully resolved particularly on the inner edge of the ditch. The baulk which had been left between had collapsed completely covering the floor so willing volunteers at the end of the season set about clearing it. This as was almost completed before the bad weather set in but at least the floor was once again revealed. However whether this remains the case is yet to be seen. Thus concluded our third season of digging, one which has revealed three more burials to add to the two discovered the previous year. Next year will see the removal of at least one of the urns and investigation of the possible cist. As usual more details of this season’s work on our Site Diary here

Thus concluded our third season of digging, one which has revealed three more burials to add to the two discovered the previous year. Next year will see the removal of at least one of the urns and investigation of the possible cist. As usual more details of this season’s work on our Site Diary here

Excavations (Season4) (Return to Index)

Further Ring Ditch Work. As usual all our Ring Ditch trenches were left open over the winter months and most survived very well. Some had seen some slippage, but only Trench 1 had once again suffered a major collapse. As we were expecting more visitors this year, it was decided to do maintenance on them so that they could be fully appreciated. The farmer had been indicating that he would likely be wanting to reclaim some of his field back at the end of the season, so this could be the last chance to see them all open.

Trench 1. Removing the fill from Trench 1 uncovered more of the flat bedrock floor and also revealed a very clear thin line of a charcoal-rich deposit in the section (which had been hinted at before). This represented the boundary between a secondary (and possibly tertiary) fill which had not been seen in other ditch trenches – samples were taken for future analysis.

Trench 6/6a This trench, the south terminus of the Ring Ditch, still had the remains of the baulk between the original Trench 6 and the later 6a. It was decided to remove it to clear up the apparent disparity between the east edges of the two trenches. This also revealed the whole of ditch’s flat bottomed bedrock floor and also, after removing a layer of stick heavy clay, bedrock in the side wall. This was similar to the situation in Trenches 5 and 5a and there was a theory that this had been placed deliberately perhaps for aesthetic reasons. It was decided not to chase the bedrock side wall for the time being as it would spoil the already excavated semi-bowl shape of the terminus.

Tenches 5/5a and 7 Some slippage in the base of Trench 5a was removed and the charcoal-rich mound in the bottom of Trench 5 cleaned up for recording. It was thought that this was perhaps a cremation burial but no cremated bone has been detected. However it was decided to leave this mound as it is for future archaeologists to investigate. Trench 7 (i.e the north Ring Ditch terminus) was also cleaned up revealing some large flat stones in the section at the bottom (again this will be left for future generations to investigate).

Trench 7 (i.e the north Ring Ditch terminus) was also cleaned up revealing some large flat stones in the section at the bottom (again this will be left for future generations to investigate).

Trench 3d This strange pit on the outer edge of the Ring Ditch in Trench 3, had more work carried out on it this year. Particular interest paid on the southwest side, expanding it to reveal more of the loose rubble. The trench was also taken down to the bottom of the pit revealing a solid bedrock floor. None of this work however has been able to answer the crucial question as to whether it was manmade or just a natural feature. The rubble in the pit and its vertical edge seem to suggest it being manmade (perhaps an earlier attempt at creating the ring ditch but in the wrong place). However the rubble seems to be continuing under the natural bedrock formation on the southeast side. It is difficult to see how that could have been achieved by human activity (unless by tunnelling) but also difficult to explain how that situation would occur naturally.

None of this work however has been able to answer the crucial question as to whether it was manmade or just a natural feature. The rubble in the pit and its vertical edge seem to suggest it being manmade (perhaps an earlier attempt at creating the ring ditch but in the wrong place). However the rubble seems to be continuing under the natural bedrock formation on the southeast side. It is difficult to see how that could have been achieved by human activity (unless by tunnelling) but also difficult to explain how that situation would occur naturally.

Trench 10 Last year this trench was opened on the east side of the central area to investigate the extent of the mottled clay and burning layers on that side. As it was so close to the projected route of our Ring Ditch, it was decided to extend it eastwards to establish the existence or otherwise of the Ring Ditch on this side (henge monuments very often have entrances on opposites sides). Without digging the whole ditch out, the inner and outer edges of the Ring Ditch were discovered more or less where we expected them to be (proving no entrance at this point).

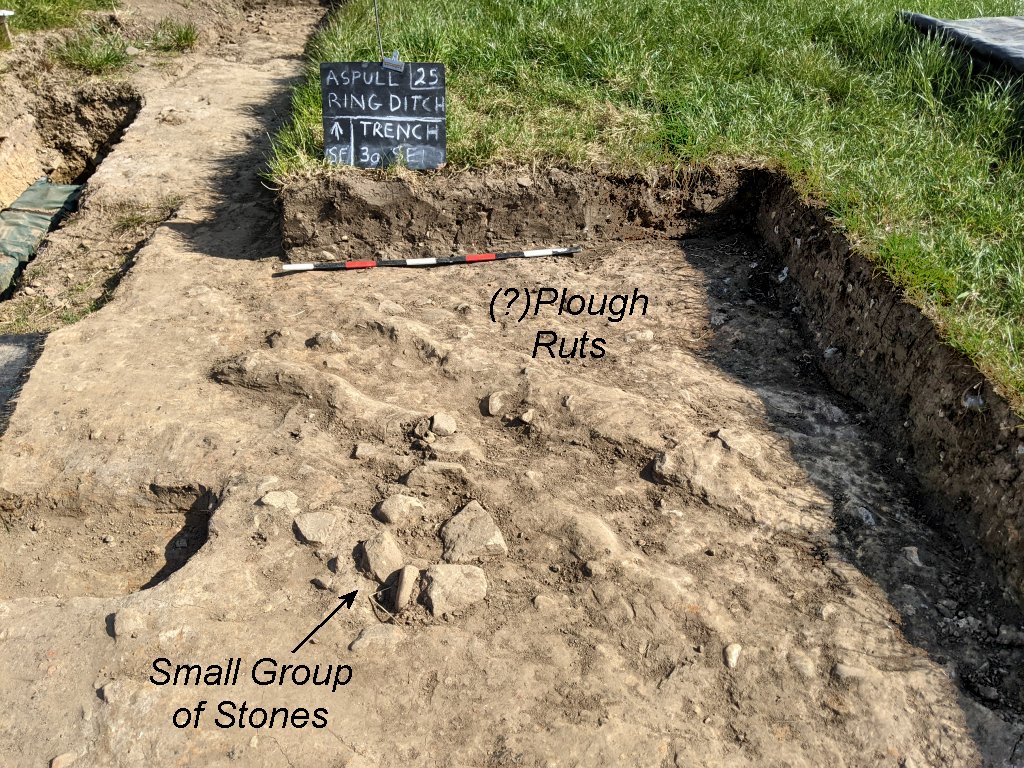

Central Area. One of the planned objectives of this year’s work was to expand our excavations in the central area to check for further burials – in particular where our first two burials where discovered (surely it wasn’t just luck that they appeared in only the second trench we dug in the central area). Around the burials we would just de-turf to reveal the mottled clay layer, but in other areas, such as between Trench 1a/1b and Trench 3a, we would check for more burials below the overlying stony layer.

As the area either side of the two burials F1 and F4 was de-turfed down the mottled clay layer, some interesting features emerged particularly on the southwest side. These included plough ruts, areas of burning and small stone clusters but no sign of any further burials.

Clay-lined Feature (F4) To get a better understanding of the structure of the mottled clay layer that our feature F4 had been inserted in, Trench 3a was extended towards it from the northwest side. This revealed a second layer of burning in the mottled clay, something that had been seen in other places but quite distinctive here. The mottled clay layer in this area was getting very confusing, so to get a better understanding of its complicated nature, a section down the southeast side of F4 was opened and the result recorded on section drawing. A small section was cut into it towards the vessel which showed that the hole detected in the sidewall came through to the outside. It also revealed that the stone base also came through to the outside of the vessel.

The mottled clay layer in this area was getting very confusing, so to get a better understanding of its complicated nature, a section down the southeast side of F4 was opened and the result recorded on section drawing. A small section was cut into it towards the vessel which showed that the hole detected in the sidewall came through to the outside. It also revealed that the stone base also came through to the outside of the vessel. The general feeling was that we should leave this feature as it was with some cremated remains in situ for future archaeologists to study. However we have been arranging with Sam Walsh, an osteologist from UCLan, to carry out a programme of analysis on our bone collections of once they have been cleaned and dried out. She indicated that she would like to see the full set of bone for each burial for her analysis, so work continued on the removal of the bone (which will have to include the removal of the central partition as bone exist below it).

The general feeling was that we should leave this feature as it was with some cremated remains in situ for future archaeologists to study. However we have been arranging with Sam Walsh, an osteologist from UCLan, to carry out a programme of analysis on our bone collections of once they have been cleaned and dried out. She indicated that she would like to see the full set of bone for each burial for her analysis, so work continued on the removal of the bone (which will have to include the removal of the central partition as bone exist below it).

Trench 3a SE Side Cleaning the surface of the mottled clay layer in Trench 3a continued all the way down to its very southeast edge (within 3m of the original Trench 3). This surprisingly revealed a stony layer. However, instead of lying on the surface of the soft sandy clay (as is the usual situation in the central area) the stones were embedded in a soft brown sandy clay layer. This was a similar situation to the stones uncovered in 2023 in Trench 1c on the northwest side of the central area. The stones had the same mottled patina and a distinctive pale green tinge with no hint of them having been affected by the burning event. A section cut through this area revealed the extent of mottled clay and burning layer, dipping down as it gave way to the soft brown sandy clay with the embedded stones in. Again this was very much like the arrangement discovered in Trench 1c. A similar situation was found last year in Trench 10 on the east side. This was reopened to investigate the extent of it, which revealed it to be quite substantial.

Again this was very much like the arrangement discovered in Trench 1c. A similar situation was found last year in Trench 10 on the east side. This was reopened to investigate the extent of it, which revealed it to be quite substantial.  There was speculation that perhaps this was an attempt to extend the central mound after the burning event and creation of the mottled clay central mound – or perhaps path around the mound but this seems unlikely as the stones were embedded rather than on the surface.

There was speculation that perhaps this was an attempt to extend the central mound after the burning event and creation of the mottled clay central mound – or perhaps path around the mound but this seems unlikely as the stones were embedded rather than on the surface.

Possible Cist Area In preparation for investigation of the possible cist feature (F11), excavations were carried out on the southwest side so that that it’s section could be recorded in a section drawing. This revealed quite a depth of stones (some quite large) and a layer of brown soft sandy clay at the lower level. This seemed to be a continuation of the layer discovered last year on the northwest side of the feature (i.e. Sondage 3a.S5 which contained flecks of cremated bone). However significantly there were no signs of charcoal in the fill which would have indicate a cremation burial.  Quite near to the cist area, a large fragment of cremated bone was found embedded in the brown soft sandy clay. This was recovered and earmarked for future dating.

Quite near to the cist area, a large fragment of cremated bone was found embedded in the brown soft sandy clay. This was recovered and earmarked for future dating.

Two Slabs Burial (F12) Work continued on removing the cremated bone from this burial discovered last year under the two large stone slabs in the northeast area of Trench 3a. Realising the size of this burial, the material was removed carefully taking out 1cm spits at a time. As the work progressed, it seemed to show there were at least two separate burials (possibly interred in bags which haven’t survived).  Again some large pieces emerged with the possibility that they weren’t fully cremated.