In 2017 we investigated a field to the west of Dark Lane in Blackrod looking for evidence of the suspected Roman road from Wigan to Ribchester. Also a possible road travelling out from Blackrod westward towards the River Douglas. The results proved inconclusive (see below) but following on from this, Alan Bury contacted us with the idea of investigating the hill on the east side of the lane. Alan had information that there used be some sort of structure on the site (Chisnall’s Summer House according to Hampson’s 1882 History of Blackrod) although nothing appears on any map. The strategic location of the hill, which is probably the highest spot in Blackrod, would also suggest that there may well have been a watch tower or signal station located on there.

East side investigations

Date: 5th November 2020

Coring Survey

Having discussed another geophysics survey of the east field with Alan Bury, it was decided that a ‘coring’ survey might be more effective (resistivity had proved unsuccessful and GPR, although likely to be able to detect the underlying rock, would be difficult to do with the condition the field as they are i.e. very bumpy and full of cow pats). Our 1 metre long corer (20mm diameter) seemed ideal for picking up the suspected ditch feature we uncovered in last year’s excavation (probing with a steel rod would also help but coring would be more reliable).

Due to this year’s virus it was only towards the end of the year that a window of opportunity presented itself i.e. when the cows had been taken in for the winter and just before new restrictions had come into force (also as we have just the one corer we only needed a couple of operatives in the field). Therefore, at short notice, Alan and I arranged to meet on a wet murky morning at the beginning of November to carry out the survey (as this was the first time we had done this type of survey, we weren’t expecting to cover a large area but the experience would be very beneficial and also help in planning future work). To see if we could detect the ditch feature uncovered in last year’s excavation, we started our first scan 2 metres north of it guided by some initial probing. Coring can be backbreaking to operate in heavy clay soils but here, the soil and subsoil is relatively soft and therefore we were able to do quite a number of cores before surrendering to our wet and aching limbs. We started with a gap of 25cm between each core but as the results became consistent we increased this to 100cm.

To see if we could detect the ditch feature uncovered in last year’s excavation, we started our first scan 2 metres north of it guided by some initial probing. Coring can be backbreaking to operate in heavy clay soils but here, the soil and subsoil is relatively soft and therefore we were able to do quite a number of cores before surrendering to our wet and aching limbs. We started with a gap of 25cm between each core but as the results became consistent we increased this to 100cm. Our second scan was located 2 metres beyond our first scan but this time we maintained a 50cm spacing. The result we obtained clearly revealed more of the rock cut feature, showing it to be over 4m wide but no more than 50cm deep. When plotted with our previous result, the pattern however suggests a shallow depression rather than ditch.

Our second scan was located 2 metres beyond our first scan but this time we maintained a 50cm spacing. The result we obtained clearly revealed more of the rock cut feature, showing it to be over 4m wide but no more than 50cm deep. When plotted with our previous result, the pattern however suggests a shallow depression rather than ditch.  Our corer was also bring up black organic material from the deepest parts which shows that it was open for a period of time before being backfilled suggesting landscaping activity at some point.

Our corer was also bring up black organic material from the deepest parts which shows that it was open for a period of time before being backfilled suggesting landscaping activity at some point.  As a coring exercise it was very useful, demonstrating that, when the conditions are right, a relatively large area can be investigated with a minimum of disruption. Alan Bury is encouraged and continues to plan further investigations. He’s also hoping to get local involvement and perhaps funding for more extensive work next year (including another dig).

As a coring exercise it was very useful, demonstrating that, when the conditions are right, a relatively large area can be investigated with a minimum of disruption. Alan Bury is encouraged and continues to plan further investigations. He’s also hoping to get local involvement and perhaps funding for more extensive work next year (including another dig).

Date: 18th September 2019

Excavation

With permission granted and a window of opportunity opening, we returned this week to excavate the field we surveyed in August. This was to see if we could get an understanding of the patterns displayed in our survey (another decent turnout with six including myself, Andy, Chris Drabble, Ken Scally, John Smalley and Alan Bury). Knowing how time-consuming marking out can be, I’d been down the previous day with Alan to mark out a 3m x 1m rectangle on a likely spot which would hopefully include features from both the survey data and the 1849 map (given time, depending on what we found, we could open another trench).  Before starting to dig however, after advise about the danger of pathogens in cow muck from our resident doctor John Smalley, we needed to clear the area of the fresh droppings 🐄(we also needed to lay a clean groundsheet to put our kit on). After removing the turf clumps of stone began to appear but it was obvious these we just lying in the topsoil, so we rapidly removed these together with the top soil until the soil colour began to change. Our excitement grew when a flat stone surface began to appear at a depth of about 20cm. Our first thought was a wall but, as the surface expanded to fill the whole of the trench on the west side, our opinion changed to it being a flagged floor.

Before starting to dig however, after advise about the danger of pathogens in cow muck from our resident doctor John Smalley, we needed to clear the area of the fresh droppings 🐄(we also needed to lay a clean groundsheet to put our kit on). After removing the turf clumps of stone began to appear but it was obvious these we just lying in the topsoil, so we rapidly removed these together with the top soil until the soil colour began to change. Our excitement grew when a flat stone surface began to appear at a depth of about 20cm. Our first thought was a wall but, as the surface expanded to fill the whole of the trench on the west side, our opinion changed to it being a flagged floor.  It appeared to be made up of small uneven flags about 30cm square on average and about 30 or 40cm thick. Very little dating evidence had emerged up to now apart from the usual late Georgian, early Victorian pottery sherds (Buckley ware) and clay pipe stem – except that is for our very first Roman related find (before getting too excited, it was just a small plastic Roman soldier, but we did enjoy the irony).

It appeared to be made up of small uneven flags about 30cm square on average and about 30 or 40cm thick. Very little dating evidence had emerged up to now apart from the usual late Georgian, early Victorian pottery sherds (Buckley ware) and clay pipe stem – except that is for our very first Roman related find (before getting too excited, it was just a small plastic Roman soldier, but we did enjoy the irony).

As we cleaned down the surface, a clear edge emerged on the east side crossing the trench at an angle northwest to southeast. this seemed to go against the general trend of the features indicated on the survey result. We continued to dig down the side of the edge on the east side of the trench to determine the full depth of the flag floor and what lay beneath it. However the edge continued, appearing to be more like a wall and we began to suspect that actually what we had was natural rock. A flag floor would surely not have this depth of stone and our suspicions were seemingly confirmed when we lifted some of the stone flags. This revealed thin layers of degraded stone dust and yet more stonework, nothing unnatural (typical of a weather flagstone outcrop).  The sharp edge, however, remained unexplained – could this be man-made i.e. a rock-cut trench? The fill would suggest that possibility being made up soft clay with flecks of charcoal in it (however being aceramic, beyond our means to date). We probed the area around to see if we could determine the extent of the feature but this proved inconclusive. The best solution would be to expand the trench and chase the feature. However our time was up having to give an allowance for back filling and returning the site to its original condition. During this exercise we were joined by a large herd of inquisitive cows being transferred by the farmer from one field to the next (loud shouting and waving of hands ensured we weren’t overwhelmed or in any danger).

The sharp edge, however, remained unexplained – could this be man-made i.e. a rock-cut trench? The fill would suggest that possibility being made up soft clay with flecks of charcoal in it (however being aceramic, beyond our means to date). We probed the area around to see if we could determine the extent of the feature but this proved inconclusive. The best solution would be to expand the trench and chase the feature. However our time was up having to give an allowance for back filling and returning the site to its original condition. During this exercise we were joined by a large herd of inquisitive cows being transferred by the farmer from one field to the next (loud shouting and waving of hands ensured we weren’t overwhelmed or in any danger).

Alan has instigated these investigations on behalf of the newly formed Blackrod Historical Society. Further work here would therefore depend on their opinion on whether there would be any merit in continuing ( a next summer community dig perhaps? possibly involving the Bolton group or even YAC (GM’s Young Archaeologists Club which is now based at Bolton).

Date: 12th August 2019

Resistivity Survey.

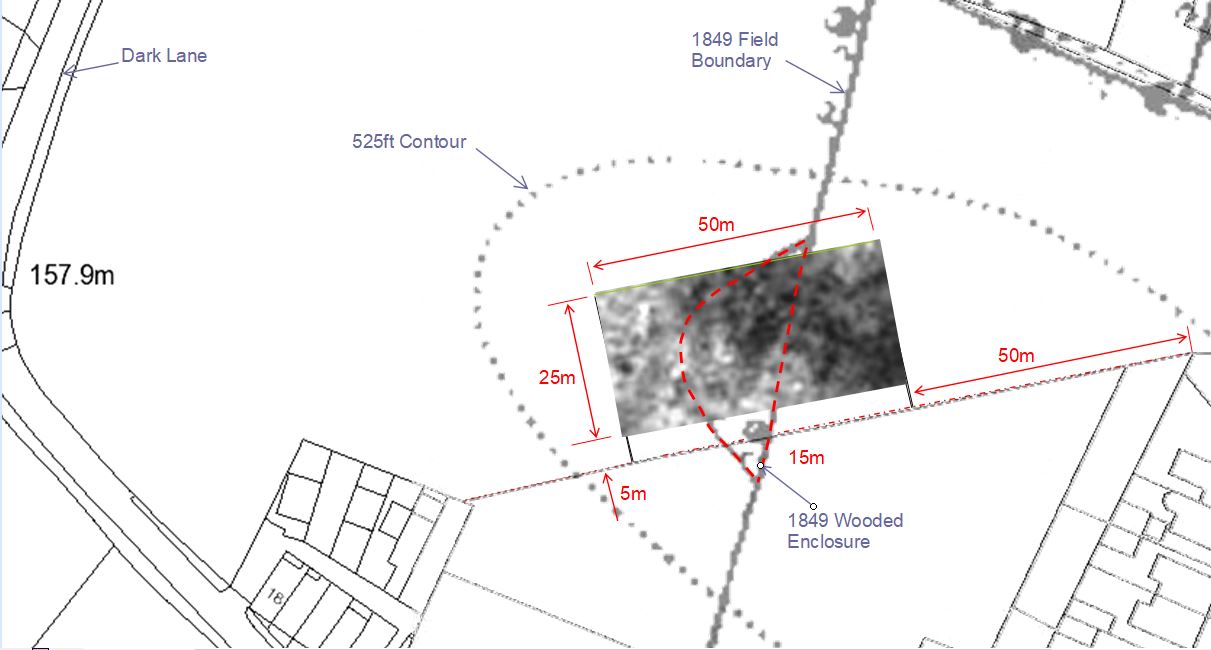

A team of five (myself, Alan, Andy Wilcock, Ken Scally and Neil Tattersall) mustered in the windswept lay-by on Dark Lane and waited for the unforcasted rain to stop☂. First task was to umph our equipment over the gate (lock having seized) and carrying it across the cowpat-strewn field (Alan had arranged with the farmer for the cows to be elsewhere). Next was to find a suitable area to survey. It was decided to located the scan as close to the crest of the hill as possible whilst still straddling the only know feature shown on early maps i.e. the small wooded enclosure abutting a no longer existing field boundary (there must have been a reason why this area had been fenced off – could there be foundations making it difficult to plough?). Using the current fence-line, crossing the field east to west, as our datum, we measured a 50m x 25m rectangle 50m from the east end and 5m into the field. We have the surveying routine off pat now so it didn’t takes us too long to complete the survey despite having to abandon it for a short while to avoid another cloud burst.  When processed however, the result proved not to be particularly enlightening, even though the range of resistivity was relatively good (with a couple of exceptions between 80ohms to 120ohms). With the eye of faith, various patterns can be discerned but whether they refer to anything archaeological it’s hard to say (dark areas are low resistance and light areas are high). Maybe ditches or walls have been detected but, as can be seen, certainly neither the wooded enclosure nor the 1849 field boundary are represented in the result.

When processed however, the result proved not to be particularly enlightening, even though the range of resistivity was relatively good (with a couple of exceptions between 80ohms to 120ohms). With the eye of faith, various patterns can be discerned but whether they refer to anything archaeological it’s hard to say (dark areas are low resistance and light areas are high). Maybe ditches or walls have been detected but, as can be seen, certainly neither the wooded enclosure nor the 1849 field boundary are represented in the result. Alan says that the land owner is not averse to allowing us to do an excavation to test one or two of the anomalies detected. It would be good to follow up with a test pit or two but, with other projects taking priority, it maybe a while before we can get around to it.

Alan says that the land owner is not averse to allowing us to do an excavation to test one or two of the anomalies detected. It would be good to follow up with a test pit or two but, with other projects taking priority, it maybe a while before we can get around to it.

West side investigations

The suspected Roman road from Wigan to Ribchester, if projected northwards through Toddington Lane, suggests it would have crossed or reached the western edges of the ridge on which Blackrod is sat. As it happens local historians, Alan Bury and his son, have been looking at early reports of a Roman road leading westerly out of Blackrod towards the river Douglas. Hampson’s History of Blackrod (1882) suggests the possibility of a Roman station around the area known as Little Scotland, quite near to a new development on Hill Lane called Romans Green (presumably on the strength of this reference). The 1840 Tithe Map for Blackrod does identify a Roman road, leading out of Blackrod to the northwest, through a farm called Goodmans Fold, but on what evidence is unclear. This is the track Alan has used for his alignment suggesting it aligns with a section of Dark Lane and then Hill Lane. It crosses our projection in a field just to the west of Dark lane. Most of the area to the north and west of Dark Lane was open cast in the 1950’s but this field seems to have escaped the destruction. Alan contacted us at the beginning of 2017 to see if a geophysics survey would turn anything up.

The 1840 Tithe Map for Blackrod does identify a Roman road, leading out of Blackrod to the northwest, through a farm called Goodmans Fold, but on what evidence is unclear. This is the track Alan has used for his alignment suggesting it aligns with a section of Dark Lane and then Hill Lane. It crosses our projection in a field just to the west of Dark lane. Most of the area to the north and west of Dark Lane was open cast in the 1950’s but this field seems to have escaped the destruction. Alan contacted us at the beginning of 2017 to see if a geophysics survey would turn anything up.

View north along the Toddington Lane alignment toward Adlington with Healey Nab in the distance and Anglezarke moors on the right.

Encouragingly, through field walking and LiDAR, Alan was able to identify at least one possibly two linear features running across the field along his alignment.

One of these features could, however, turn out to be remains of a temporary path put in when the field boundary and right-of-way path were both removed from the adjacent field. The current path and right-of-way has now been reinstated down fence line on the south side of the field.

It was only at the end of the year in November 2017 that we were able to arrange a survey of the field but we were able to use both resistivity and GPR. Unfortunately the GPR machine available from Sygma was only capable of 2D scans, which meant an area survey with this machine was not possible. However, it did mean we could cover a much larger area. Here are the results of our surveys.

Resistivity Disappointingly nothing showed up on our alignment – not even the old 1849 field boundary. However it seems the temporary path was detected and Alan was encouraged by two features seemingly running roughly in the direction of his alignment, although these look suspiciously like field drains. Just to note, the dark patch on the right side of the scan indicates an area of low resistivity which is probably due to water collecting where the field drops away it a shallow hollow.

Disappointingly nothing showed up on our alignment – not even the old 1849 field boundary. However it seems the temporary path was detected and Alan was encouraged by two features seemingly running roughly in the direction of his alignment, although these look suspiciously like field drains. Just to note, the dark patch on the right side of the scan indicates an area of low resistivity which is probably due to water collecting where the field drops away it a shallow hollow.

GPR We carried out a number of scans across the field, all however with similar results. The best was this long scan across the diagonals of the field which was intended to capture both alignments.

We carried out a number of scans across the field, all however with similar results. The best was this long scan across the diagonals of the field which was intended to capture both alignments.  Again the only thing that showed up was in the area of the temporary path, although it does indicate something that is more than 10 metres in width and at a depth of between 30cm and 60cm. This is substantial bigger than a path but whether it’s anything of particular significance, only an excavation will tell. Fortunately Alan has secured permission from the landowner for a dig which hopefully we will be able to carry out next year.

Again the only thing that showed up was in the area of the temporary path, although it does indicate something that is more than 10 metres in width and at a depth of between 30cm and 60cm. This is substantial bigger than a path but whether it’s anything of particular significance, only an excavation will tell. Fortunately Alan has secured permission from the landowner for a dig which hopefully we will be able to carry out next year.