Chapters

|

Project: Wigan Pier

Wigan Pier |

by Derek Winstanley

with help from Bill Aldridge

(Wigan Arch. Soc.) 2015 |

Introduction

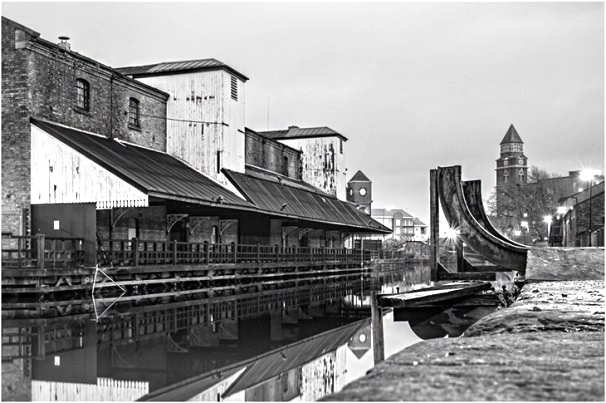

Wigan pier is an iconic landmark, famous worldwide. There are many different stories about the pier. It is not surprising that for a town more than 20 miles from the sea, Wigan pier gained notoriety through music hall songs and jokes by George Formby Sr. (Photo 1) and George Formby Jr. (Photo 2); George Jr. was born in Wigan.

Photo 1. George Formby Sr. Photo 1. George Formby Sr. |

Photo 2. George Formby Jr. Photo 2. George Formby Jr. |

Photo 3. George Orwell Photo 3. George Orwell |

George Orwell regarded the working class, for whom he had great admiration, as victims of injustice and visited Wigan in 1936 to see what their lives were like. Although he wanted to temporarily be part of their world, he knew he was not one of them and, "went among them as a foreigner"(GO 1937). He searched in vain for a real railway pier head in the Canal Basin, but it had been demolished in 1929.

Nevertheless, in 1937 Orwell published his landmark book, "The Road to Wigan Pier". Riding on the notoriety of the then non-existent pier, a symbolic replica of a tippling mechanism was installed on the canal wharf in the 1980s (Photo 4). A night club, a pub and a display to document Wigan's history, "The Way We Were Heritage Centre", thrived by the canal for quite a few years. Today, a 10-year plan is being developed to reinvigorate Wigan Pier and the canal area.

|

Photo 4. Wigan Pier Photo 4. Wigan Pier

In 1980, Hannavy and Winstanley (ref) prepared a book on Wigan Pier to present a vividly illustrated account of the pier: sixty six photos provide an historical treasure trove. However, few references are provided and some important historical documents apparently were not utilized. This paper builds on this book and corrects some of the errors.

In searching to establish the facts about the pier, we find that there were, in fact, three piers and a dock in the area of today's Wigan Canal Basin. This paper documents the history of these waterway structures as integral parts of the town's transformation from a market town, with craftsmen and merchants, to a leader in the Industrial Revolution.

|

Founded on Coal

Coal has been mined in the Wigan area for hundreds of years, perhaps as far back as Roman times. However, coal production in the Wigan area in the early 1700s was only a few thousand tons per year and the population of the town only a few thousand. Demand for coal was not great, technology only allowed for shallow mining, and transport was primitive. Sinclair (1882, Vol. 2, 202) reports that,

"Strings of pack horses, thirty and forty in a gang, were used for carrying coals and lime. They were obliged to make way for each other by plunging into the side road (which was soft and sometimes almost impassable), out of which they found it difficult to get back upon the causeway" Whittle cited in Hardwick, "History of the Borough of Preston and its environs: in the county of Lancaster" (p. 383) "On review of the past it was evident that none of the local resources had been fully developed, and that all seemed content to jog along as their fathers had done before them."

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to progress was the manorial system of governance that had dominated Wigan politics, business and religion since imposition of Norman rule in 1066. The Rector of Wigan Parish Church also was Lord of the Manor. In that capacity, he granted pieces of land and privileges to a small number of selected people - burgesses -, while the majority of Wiganers had few rights. Sinclair describes in detail the power structure and its restrictive impacts on innovation in the early 18th century:

"They were shut up in themselves by the spirit of protection, and enterprise had been foreign to their nature." (202) "All who were not naturalised townsmen, or who were the offspring of aliens, were called foreigners, and laws concerning these foreigners were of the strictest nature." (145) "Although in olden times, as a walled town, Wigan was a refuge for runaway slaves and foreigners, the burgesses seemed to have always had a very strong antipathy to strangers settling in their midst, and their reasons for it are very evident. They were clothed in that little authority which gave them power to accept or reject whomsoever they pleased; as burgesses they were strong political sectarians, who valued their burghal rights perhaps as much as any foreigner or barbarian of the middle ages ever did his freeborn citizenship of Rome, and, consequently, were loth to bestow them promiscuously on aliens; above all, from a purely protective spirit, they believed the granting, or rather selling, of freedom the best means of bringing wealth to the borough." (230).

Perhaps due to recognition that Wigan was slipping into the backwater of a new system of growth, capitalism and free trade that was emerging in England, some burgesses slowly became more receptive to change. Change was realized by a few Wiganers and an increasing number of 'foreigners' who began to break down age-old traditions and barriers. The pace of change became so overwhelming that, with no strong alternative path to development, laissez-faire capitalism and free trade began to shape Wigan's economic, social and environmental development.

Wigan is in the middle of the Lancashire Coalfield. It was landlocked with no easy means of transporting large quantities of coal to growing markets. Construction and utilization of new transport arteries - waterways and later railways - were desperately needed for Wigan and surrounding townships to develop and market their rich resources.

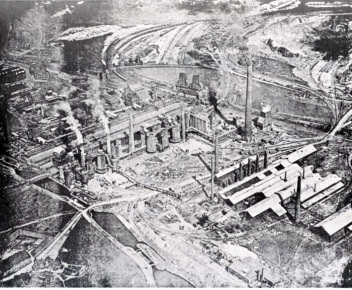

If you were born in the Wigan area in the 19th and 20th centuries, there was no question about the dominance of coal mining - pits, spoil heaps and steam locomotives were everywhere. A defiled landscape with flashes (Photo 6), caused by extraction of millions of tons of coal underground, and spoil heaps (Photo 7), caused by dumping vast quantities of mining waste on the surface, became visible signs of laissez-faire development. A huge iron works mushroomed across the landscape (Photo 8) and cotton mills sprang up everywhere (Photo 9).

Photo 8. "Top Place" Iron Works

Photo 8. "Top Place" Iron Works

|

Photo 9. May Mill.

Photo 9. May Mill.

The last working cotton mill in

Wigan which closed in 1980.

|

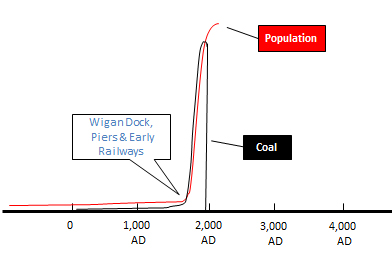

But our lives are short and it is revealing to take a longer time perspective to coal production and population growth in the Wigan area (Fig 1). Starting in the late 18th century, rapid population growth paralleled the enormous increase in coal production. Wigan dock, piers and early railways facilitated these revolutionary changes. When coal production peaked in the early 20th century, and ceased before the end of the century, the population became disconnected from coal production; today, population in the Wigan area continues to grow, albeit at a much slower pace.

Fig 1. The construction of Wigan dock, piers and early railways in relation to coal production and population growth in the Wigan area.

Fig 1. The construction of Wigan dock, piers and early railways in relation to coal production and population growth in the Wigan area.

|

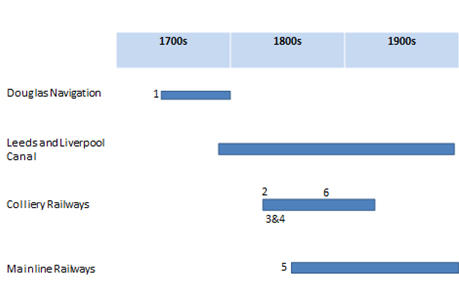

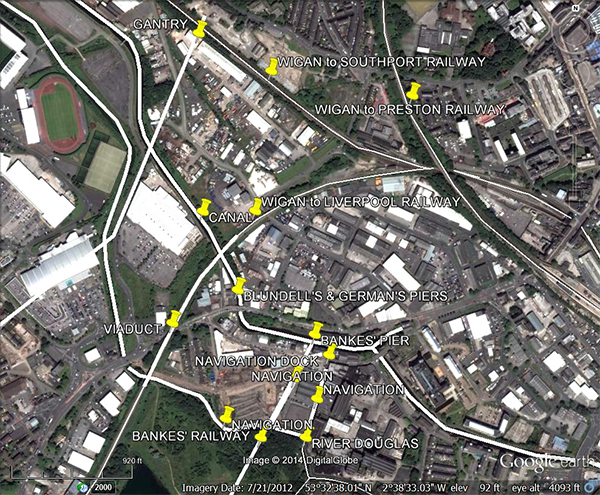

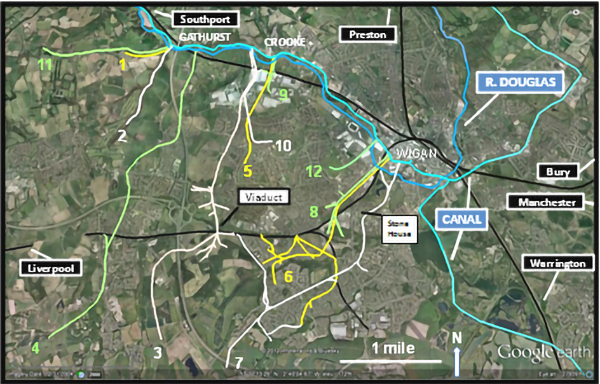

Fig 2 shows the chronology of major developments that forged the creation and folklore of Wigan piers and dock. Fig 3 shows the locations of the transport arteries, the piers and the dock. The rest of the paper provides more detailed information on these developments, based on early maps and historical documents.

Fig 2. The evolution of transport systems relevant to Wigan piers and dock.

Fig 2. The evolution of transport systems relevant to Wigan piers and dock.

- Douglas Navigation Dock (1742) on Pottery Road.

- Claughton/Daglish-Brimelow/Daglish/Bankes Pier (1822) on the canal in the Potteries.

- Germans' Pier (c.1825) on the canal by Seven Stars Bridge.

- Blundell's Pier (c. 1827) on the canal by Seven Stars Bridge.

- Wooden viaduct for the Wigan to Liverpool Railway (built 1848 and filled c.1890).

- Overhead tubway on wooden gantry from Newtown Colliery to Meadows Colliery (c.1888 to c.1910).

|

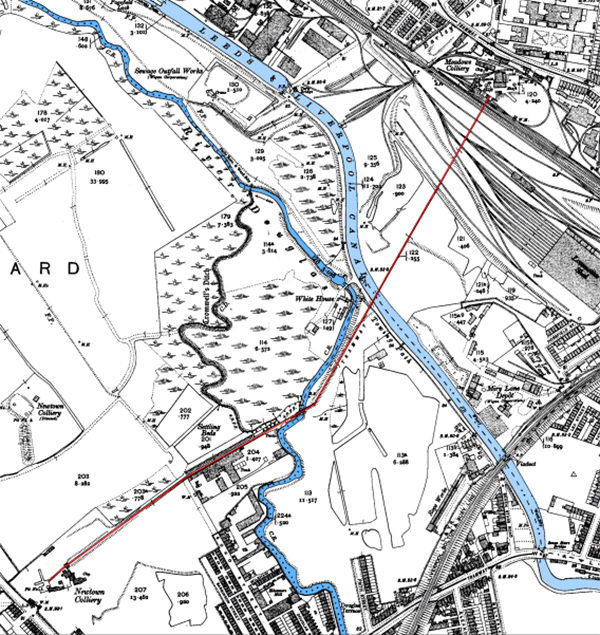

Fig 3. Location of the Douglas Navigation and Dock, the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, railways, Bankes', Germans' and Blundell's Piers on the canal, a pier-like gantry and a wooden viaduct.

Fig 3. Location of the Douglas Navigation and Dock, the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, railways, Bankes', Germans' and Blundell's Piers on the canal, a pier-like gantry and a wooden viaduct.

|

|

Douglas Navigation

The first major transport development was authorization of The Douglas Navigation in 1720 (MC - DN). As per tradition, conservatism and quiescence prevailed for many years and little work was done. "The great awakening effort at enterprise of 1720 seemed to be choked at its very birth by the failure to carry out the Act for navigating the Douglas, and the wonder is, not so much that it died, or declined then, but rather that the naturally conservative spirit of Wigan ever allowed the idea to become an Act." (Sinclair Vol. 2, 220).

Around 1737, Alexander Leigh and his father-in-law, Robert Holt, took the bull by the horns and pushed construction along rapidly. Both Leigh and Holt served as mayor of Wigan on multiple occasions. To make the River Douglas navigable from Wigan to the Ribble Estuary, sections had to be canalized and locks and weirs constructed. The Douglas Navigation opened in 1741 and was finished in 1742, allowing boats to carry some 20 tons of coal and other goods some 10 miles to the Ribble Estuary and beyond. Boats from Wigan to Gathurst and Parbold were 'bow hauled' by gangs of men. There, the coal was trans-shipped to sailing 'flats' which sailed into the Ribble Estuary (H&W). Returning boats carried limestone, flags, paving stones and slate for building materials and lime for farmers' fields. There were also two pleasure boats on the navigation. It cost £9,866 to make the river navigable, five-sixths of his being borne by Alexander Leigh. In 1771 Alexander Leigh sold all his shares to the newly-formed Leeds and Liverpool Canal Company. The Douglas Navigation certainly provided stimulus to open Wigan to broader markets, but the Ribble Estuary area was not well developed and Liverpool was receiving coal from the much closer collieries in Prescot. When the Leeds and Liverpool Canal was finished to Wigan in 1794 (see below), the navigation was effectively abandoned. (Anderson; Leigh Oxford DNB; Langton 1979; MC 8/26; MC 8/28/14

Alexander Leigh was a Wigan barrister and sometime mayor of Wigan. He bough Hindley Hall (Hindley) in 1720 but never lived there. It was left to his grandson Robert Holt Leigh who moved there when he became MP for Wigan in the early 19th century, rebuilding the Hall in 1811 (see Note 1).

We do not have a map of the Douglas Navigation in Wigan in the 1700s. However, information can be gleaned about the navigation from historical sources. Whitaker (1755, 37, 44-45) states that c.1735, when the navigation was being constructed, substantial evidence of a major battle between Britons and Saxons was discovered. Whitaker states that the battle was probably fought in the marshy Parson's Meadow on the south side of the River Douglas. A large number of horse and human bones, spurs and an amazing quantity of horse shoes (some 500-600 lbs in weight) were discovered, "All along the course of the channel from the termination of the Dock to the point of Pool-bridge, for forty or fifty roods [~250-300 yards] in length and seven or eight yards in breadth..." According to Whitaker, the legendary King Arthur was victorious in this battle; others believe it could have been a Norman or Civil War battle. Irrespective of the battle, questions arise as to the location of the dock and Pool Bridge.

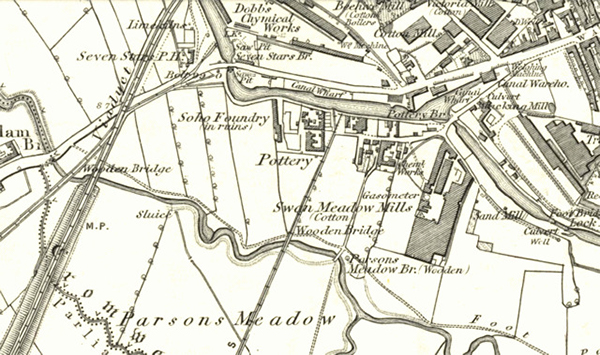

On the 1802 Canal Survey Map (Fig 4), Parson's Meadow is shown as Reverend George Bridgeman's land. Burgage plots - strips of land belonging to the burgesses - are shown clearly on this map and on the 1849 Ordnance Survey map. The 1802 map also shows two canalized channels, or cuts, branching northwards off the River Douglas between two potteries, one owned by Mr. Leigh. The description of a channel for some 40-50 roods from the dock is consistent with the length of both channels shown on the 1802 map. These two canalized channels are not shown on the 1832 Boundary Commission Map, so they must have been filled before surveying was conducted. The 1802 map shows some five buildings at the terminal point of these two canalized sections, so it is reasonable to interpret that these buildings and canalized channels formed the end section of the Douglas Navigation and the site of Wigan Dock.

Fig 4. Canal Survey Map, 1802. - courtesy of Mike Clarke (rotated through 90° to give it the correct geographic orientation).

Fig 4. Canal Survey Map, 1802. - courtesy of Mike Clarke (rotated through 90° to give it the correct geographic orientation).

|

Pool Bridge probably was the name for the wooden bridge across the River Douglas shown on the 1849 and subsequent Ordnance Survey (OS) maps and town plans as Parson's Meadow Bridge. Parson's Meadow Bridge is at the southern end of what is Pottery Terrace today. A short distance upstream of the bridge, Poolstock Brook flows from Poolstock into Smithy Brook, which in turn flows into the River Douglas.

A key unresolved issue is whether the Leeds and Liverpool Canal Basin was built specifically for the canal in the 1780s and 1790s, or whether it represents a slightly modified older terminal basin built for the navigation. Mike Clarke, a canal expert, believes the latter. Complications arise in interpreting the sequence of developments from the navigation to the canal, because the 1802 map was drawn a decade after the Leeds and Liverpool Canal was constructed and the map shows the canal, the canal basin and the navigation. On the 1802 map, the buildings at the end section of the Douglas Navigation are shown to be on, or close to the canal wharf. However, navigation buildings close to the later canal do not necessarily mean that the north-south canalized channels joined an earlier basin constructed for the navigation.

Mike Clarke acknowledges that early accounts of the navigation are difficult to interpret and speculates that in constructing the navigation there was, "Work on the cut above Pool Bridge, probably the terminal basin..." (ref).This assumes that there was a terminal basin for the navigation, separate from the Dock referred to by Whitaker. A corollary of this assumption is that, if there was a navigation basin, it must have been connected to the River Douglas some distance to the west via a canalized channel from Seven Stars Bridge [Wigan Bridge on the 1802 map]. However, there is no evidence of such a canalized channel.

We find no evidence of a terminal basin for the navigation on the site of the canal basin, but there is evidence of terminal dock area at the end of the two cuts shown on the 1802 map. Our interpretation is that the two north-to-south canalized channels, or cuts, shown on the 1802 map, together with the buildings at the northern end represented the terminal dock area for the Douglas Navigation in Wigan. It is probable that the canalized section shown on the 1802 map at the eastern end of the basin fed water into the north end of the navigation, and later into the canal basin. It is also possible that, when the canal basin was built, there may well have been an existing extensive large ditch created from clay extraction for the potteries.

In the 1770s, wooden railways were constructed from the coal mines in Orrell down to the navigation in the Dean-Gathurst-Crooke area, a few miles west of Wigan. This is when pier heads started to appear in the Wigan area; pier heads were coal loading staithes, probably wooden jetties, where wagons from nearby collieries were unloaded into waiting boats on the navigation. Each colliery had its own private railway and pier head, and some had their own boats. However, the demand for coal in Liverpool, Ireland, north Lancashire and overseas was beginning to exceed the capacity of the navigation to transport increasing quantities of goods. For the Wigan area to achieve its potential in marketing its rich resources, a new transport artery had to be developed.

|

Leeds and Liverpool Canal

The original bill authorizing the Leeds and Liverpool Canal was passed in 1770. Holt Leigh, son of Alexander Leigh, went to London to represent his father during the committee stage; the journey to London took him three and a half days (Anderson). Jonathan Blundell, a Liverpool merchant, who founded a colliery in Orrell and later the huge Pemberton Colliery, served on the canal management committee and negotiated the purchase of the Douglas Navigation in 1771 (Anderson).

The canal opened in 1774 and provided direct access to the emerging Liverpool market; at that time it included the Douglas Navigation from Dean to Wigan (L&LC Soc). In 1776, the canal section from Dean to Wigan was authorized and in 1780 Wigan Bridge, today known as Seven Stars Bridge, was built (personal communication Mike Clarke, 8/26/14. It was in 1794 that the Wigan to Dean section of the canal took over from the Navigation [MC]. Horse-drawn barges now could transport 60 tons of goods on the canal (H&W).

The canalized sections of the navigation connecting Wigan Dock to the River Douglas must have been filled in the early 19th century. The entire length of the canal was finished from Leeds to Liverpool in 1816[L&LC site]. The original canal warehouse with stone-mullioned windows, built c.1780, is on the north side of the canal, opposite the canal junction (MC 8/12). In 1820 the branch of the canal from Wigan to Leigh was opened (L&LC site); in Leigh it links with the Bridgewater Canal and a larger canal network. The end warehouse (Wigan Pier 1) covering the canal arm was built c.1825 (MC 8/12/14).

A few miles to the west of Wigan, Winstanley Hall and Winstanley Estate had been the home of the Bankes family since 1595. Small quantities of coal had been mined on the estate by the Winstanleys prior to the sale to the Bankes, and the Bankes family continued to mine small quantities of coal. Starting in the late 1700s, the Bankes family accumulated wealth from leasing land to Jonathan Blundell and other investors, particularly John Clarke, a wealthy Liverpool banker.

William Clarke, John Clarke's father, opened the first bank in Liverpool in 1774. His sons, John and William, joined their father as co-owners in 1777 (Hughes, 1906). The bank, like most enterprises in Liverpool, prospered from the slave trade (Winstanley 2014; 2015). John soon decided to team up with William Roscoe, a Liverpool banker and an abolitionist, to open a colliery in Orrell in 1789. Here they partnered with William German and Charles Porter, who were local entrepreneurs and colliery owners. In 1792, John Clarke, his brother William and William German signed a 20-year lease to mine coal in Winstanley, which lead to construction of the Arches Viaduct (Anderson OCF) In January 1812, Robert Daglish, Clarke's Colliery manager, built at Haigh Foundry and put into operation in Winstanley and Orrell in January 1813 the first steam locomotive in Lancashire and the third commercially successful steam locomotive in the world - The Walking Horse (see Note 2). The Earl of Balcarres of Haigh Hall owned the Foundry at the time (Winstanley 2014) (see Note 3).

Wigan and surrounding townships thus began to be transformed by a small number of influential people who developed waterways to transport coal from their collieries, especially in Orrell, Winstanley and Pemberton. These early developments occurred to the west of Wigan, rather than in Wigan, mainly because high quality coals in the Winstanley and Orrell Coalfield occurred near the surface, were relatively easy to mine, and commanded high prices. Fig 5 shows the location of early colliery railways west of Wigan.

Fig 5. Early colliery railways west of Wigan (modified DW 2014).

Fig 5. Early colliery railways west of Wigan (modified DW 2014).

|

|

The First Documented Wigan Pier

This section identifies the earliest evidence related to the construction of a pier head for unloading or tippling coal from colliery railway wagons into canal barges in the Wigan canal basin. Joyce Bankes of Winstanley Hall wrote the authoritative paper on, A nineteenth century colliery railway operating from Winstanley to the canal in Wigan (Bankes 1962). Unless otherwise stated, the information in this section is taken from Bankes' paper.

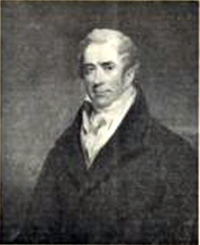

It was in 1819 that Thomas Claughton, a Warrington solicitor, salt maker and coal mining speculator, who served as Member of Parliament for Newton, purchased Stone House, on Warrington Road. Land speculation fever was in high gear. Meyrick Bankes Sr., (Photo 10), Squire of Winstanley Hall (Photo 11), owned the mineral rights for Stone House Estate, between Worsley Mesnes and Goose Green. In 1822, he sold a portion of the mines and leased mineral rights to Thomas Claughton. About the year 1808, he began to live in Haydock Lodge (Photo 12), which was owned by Thomas Legh of Lyme Hall in Cheshire (see Note 4). The same year, Claughton contracted with various parties for a pier head on the canal, but then sold a portion of his mines and mineral rights to John Daglish. John Daglish entered into partnership with Peter Brimelow, a coal master of Wigan, and together they operated Stone House Colliery.

Photo 10. Meyrick Bankes, Sr.

Photo 10. Meyrick Bankes, Sr.

|

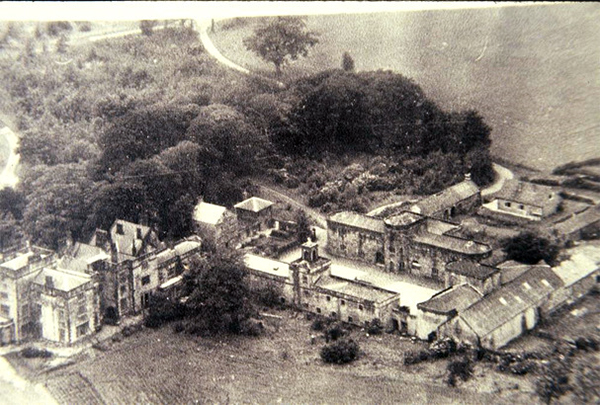

Photo 11. Winstanley Hall

Photo 11. Winstanley Hall

(Derek Winstanley Collection)

|

Photo 12. Haydock Lodge

Photo 12. Haydock Lodge

|

John Daglish and Peter Brimelow purchased Stone House Estate and the railway in 1830. John Daglish was brother of Robert Daglish, who built The Walking Horse. In 1840, John Daglish became the sole proprietor of the estate and railway. In 1842, he agreed to sell to Meyrick Bankes Jr. his railway to the pier head on the canal, including the weighing machine and tippler. After leasing land to entrepreneurs for many decades, the Bankes family had accumulated sufficient wealth to now operate their own colliery in Winstanley. In 1845, Meyrick Bankes Jr. opened a new 31/2 mile railway line from his Winstanley pits to the pier head on the canal in Wigan, including the section of railway he purchased from Daglish (No. 7 in Fig 5). In 1850, the lease for Stone House Colliery passed to Dr. George Daglish, eldest son of Robert Daglish. The pier itself apparently was owned by a conglomerate of wharfside interests and it was only in 1850 that Meyrick Bankes Jr. finally bought Thompson's Pier Head; John Thompson, an iron merchant, represented the iron industry along Pottery Croft Wharf.

In review, Joyce Bankes documents that in 1822 Claughton contracted to build a pier head on the canal, but there is no evidence that he actually built a pier head in the few months before he sold out to John Daglish. However, the Lancashire Record Office does hold documents in which it states that John Daglish, "hath made and erected a weighing machine, a pier head and tippler upon or near to the banks of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal in Wigan aforesaid" (personal communication Richard Daglish, January 12, 2015). After careful consideration of historical literature, we conclude that John Daglish built the first Wigan pier c.1822. The current symbolic tippler is located at the site of the original pier head and tippler on Pottery Croft Wharf.

It seems reasonable to assume that when the canalized sections of the abandoned Douglas Navigation were filled, the colliery railway line was constructed down to the canal along the filled-in west cut of the canalized Douglas Navigation. The railway is shown clearly on the 1849 OS map (Fig 6) and the east filled-in canalized section of the navigation terminal appears as a narrow road.

Fig 6. Six inch OS Map - first published in 1849 (this is a later edition dated to 1864).

Fig 6. Six inch OS Map - first published in 1849 (this is a later edition dated to 1864).

|

After half a century of accumulating wealth from leasing land to entrepreneurs, such as John Clarke and Jonathan Blundell from Liverpool, the Bankes family returned to what the Winstanley and Bankes families had done for centuries before - they established a colliery themselves. This time, the scale of coal mining and the financial rewards were much larger (see Note 5).

Bankes' Railway was laid with T section wrought iron rails, supported on stone sleeper blocks. This 4 ft narrow-gauge railway utilized gravity and horse power to transport coal from Winstanley down to the canal. Joyce Bankes provides a drawing of a double-horse truck, or "dandy cart" used on the railway. Most of the railway to the canal was downhill and the horses got a free ride; they earned their oats by pulling the empty wagons uphill to Winstanley. In 1882, Meyrick Bankes introduced a narrow-gauge steam locomotive, Louisa. In 1885 Bankes' Winstanley Colliery was leased to Winstanley Collieries Co. Ltd. In 1886/87 the narrow-gauge line down to the canal was changed to standard gauge and a standard-gauge steam locomotive was introduced, making Louisa redundant. A new standard gauge steam locomotive, Eleanor, took over and was later joined by several other locomotives, including Winstanley, a four coupled saddle tank locomotive, in 1905 (Photo 13).

Photo 13. Standard gauge steam locomotive "Winstanley" on Winstanley Colliery Railway, 1905 (Derek Winstanley collection).

Photo 13. Standard gauge steam locomotive "Winstanley" on Winstanley Colliery Railway, 1905 (Derek Winstanley collection).

|

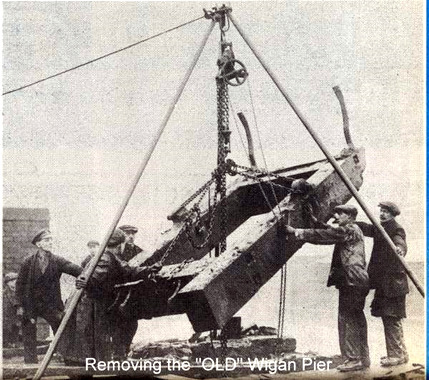

The 1890 Town Plan (Fig 7) shows that on the south side of the canal basin there are two what appear to be shunting lines to the east of two railway lines to Bankes' Pier Head, which is shown as a promontory onto the canal. On one of these lines to the pier head is a weighing machine and at the pier head there is a windlass for tippling coal wagons into canal barges. A wooden bridge takes the single line railway across the River Douglas. Following closure of Leyland Green Colliery in 1927, the tippler on the pier head in the Potteries was demolished in 1929 (Photo 14).

Fig 7. Town Plan, 1890.

Fig 7. Town Plan, 1890.

|

Photo 14. Removing "Old" Wigan Pier (Ron Hunt collection)

Photo 14. Removing "Old" Wigan Pier (Ron Hunt collection)

|

|

Germans' and Blundell's Piers

Independent railways from Germans' Colliery, in the Goose Green/Newtown area, and Blundell's Pemberton Colliery were constructed c.1825-28 along what today is Victoria Street to separate terminals, or pier heads, on the canal near Seven Stars Bridge (Anderson - Blundells; TSP). An 1802 map (Fig. 4) shows coal yards on both sides of the canal, just to the north side of Wigan Bridge; it was probably the coal yard on the west side of the canal that became the site of Germans' and Blundell's pier heads. Both railways were narrow gauge, probably 4 feet, laid on iron edge rails and worked by gravity and horse power; they did not use steam locomotives, nor did they convert to standard gauge (Anderson OCF; Blundells. TSP). Both railways were abandoned in the 1860s (TSP).

William German established coal mines in Shevington in the 1780s, and in 1789 he partnered with John Clarke and William Roscoe to purchase Crooke and Crooke Hall. This was a prime example of Liverpool entrepreneurs partnering with a well-established local coal master to open up coal mining in the Wigan area. The German family operated pits in Pemberton before 1795 (Anderson - Jonathan Blundell & Son, Wigan Library WTN 623) and in the early years of the 19th century the German family bought a group of coal pits extending from Goose Green to Newtown (SPT). In 1825 or 1826, the German family constructed a one and a half mile narrow gauge railway from their colliery down to the canal (TSP) (No. 8 in Fig 5).

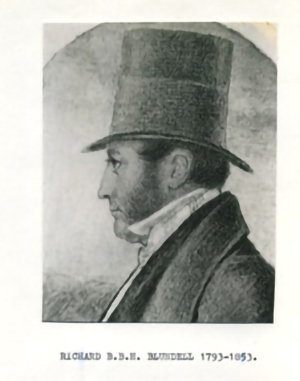

Photo 15. Richard Benson Hollinshead Blundell (Derek Winstanley Collection).

Photo 15. Richard Benson Hollinshead Blundell (Derek Winstanley Collection).

|

It was Richard Benson Hollinshead Blundell (Photo 15), son of Henry Blundell, grandson of Jonathan Blundell and great grandson of Bryan Blundell of Liverpool, who built the railway from Pemberton Colliery c.1827 (Anderson - Blundells) (No. 6 in Fig 5). Blundell's Railway paralleled Germans' Railway along present day Victoria Street to the canal (see Note 6). In 1835, coal output at Blundells' Pemberton Collieries was 51,000 tons (Anderson, BC). It is reasonable to assume that the coal was transported to the canal on the early railway. As technology improved, the demand for coal increased and mainline railways took over, production at Pemberton Collieries increased to 703,000 tons in 1913 (Anderson BC).

|

|

Folklore, music hall and literary influences

It is probably true to say that in the absence of George Formby Sr. and George Orwell, Wigan piers would have been lost in obscurity. It was in the late 1800s and early 1900s that George Formby Sr. (Photo 1) sang songs and told music hall jokes about a Wigan pier. George Sr. was born James Lawler Booth in Ashton-under-Lyne in 1875. His son, George Formby Jr. (born George Hoy Booth in Wigan in 1904), took to the music hall stage in the early 1900s (Photo 2).

Two stories relate to the music hall Wigan Pier. The first story is that, according to the lyrics of a George Formby Sr. song, on pulling out of Wigan Northwestern Railway Station bound for Blackpool, he looked down on Wigan and observed a long, wooden, pier-like structure. Mike Clarke believes that it could have been the East Lancashire Railway's wooden viaduct, which extended some 500 yards from near Miry Lane to the River Douglas on the Bury to Liverpool Railway. The six inch OS map (Fig 6) shows a lengthy viaduct at this location. The wooden structure was filled, probably in the late 1880s, to form an embankment for the then Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. However there is some doubt to this story as it would not have been easy for Formby Sr. to see this long wooden viaduct even if his seat on the train was facing towards Wigan.

The other story, according to Robert Taylor, one-time stationmaster at Wigan, is that in 1891, not long after leaving Wallgate Station, an excursion train from Wigan to Southport, was delayed on the outskirts of Wigan and passengers saw a long wooden structure that reminded them of Southport Pier. This structure would have been the 1,050 yard long wooden gantry shown on the twenty five inch OS map (Fig 8). It was built in the late 1880s and carried a double line of rails from Lamb and Moore's Newtown Colliery high across the River Douglas, the canal and the Wigan to Southport Railway line, to Meadows Colliery by Frog Lane (Hannavy, 1990). It certainly would have been easy to see this wooden gantry from a train heading towards Southport.

Fig 8. Twenty Five inch OS map (1910) - wooden gantry shown in red (Wigan Arch. Soc.)

Fig 8. Twenty Five inch OS map (1910) - wooden gantry shown in red (Wigan Arch. Soc.)

|

It thus appears that the music hall Wigan Pier originated as reference to one of these two structures (with the latter being most likely) and was made famous in songs and jokes and in George Orwell's 1937 book. "The Road to Wigan Pier". In 1936, when Orwell spent time in Wigan, neither of the wooden piers nor any of the railway pier heads, or tipplers, had survived.

|

Conclusions

The transformation of Wigan from a market town to a powerhouse in the Industrial Revolution was achieved by enterprising capitalists harnessing scientific and engineering developments to mine coal and improve transportation systems. The Douglas Navigation and the Leeds and Liverpool Canal dominated the transport system during the early stages of Wigan's transformation in the 18th century. Starting in the 1770s, private colliery railways replaced horses and carts for transporting coal to the waterways and were the forerunners of mainline railways, which largely took over from the waterways starting in the 1830s. The mainline railways greatly expanded the markets for Wigan area coal. Most collieries began to convert parts or all of their railways to standard-gauge steam locomotives, which connected directly to the new standard-gauge mainline railways. By the mid-1800s, coal was being mined down to almost 2,000 feet and coal production increased dramatically.

History reveals that Wigan's first 'maritime' structure was a dock at the head of the Douglas Navigation, built about 1740. By the 1820's, there were railway pier heads at three locations in the Wigan Canal Basin. John Daglish built the earliest documented pier head with a tippler and weighing machine on the site of the current symbolic replica of a tippler c.1822. This is where horse-drawn coal wagons on a narrow-gauge railway from Daglish's Colliery in the Worsley Mesnes/Goose Green area tippled coal into canal barges. Over the next half century, the narrow-gauge railway and horses gave way first to a narrow-gauge steam locomotive in 1882 and to a standard-gauge steam locomotive c.1886 as Meyrick Bankes Jr. extended the railway to serve his Winstanley Colliery. As the railroad transported coal from Winstanley to the canal, it can be said that the road to Wigan Pier started in Winstanley.

The pier heads for Germans' and Blundell's Railways, near Seven Stars Bridge, were the second and third Wigan piers to be constructed in the Wigan Basin in the md-1820s. These horse and gravity colliery railways lasted for 40 years.

Music hall songs, jokes and folklore leave open the possibility that two different wooden railway structures were interpreted as piers in the late 19th century: a wooden viaduct crossing the canal and River Douglas just to the north of Seven Stars Bridge, but perhaps most likely a high wooden gantry from a colliery at Newtown to a colliery in Frog Lane,

The tippler on Pottery Croft Wharf in Wigan basin remains an appropriate site for celebrating a rich history of Wigan piers and dock and a symbol of Wigan's transformation. As plans are developed to renovate the Wigan basin area, it would be worthy of its iconic place in world history to erect a full reproduction of the end section of the colliery railway, including a pier head, coal wagons pulled either by a horse or a steam locomotive, and a tippler unloading a wagon full of coal into a waiting canal barge.

We end by revisiting the big picture that Orwell painted of the Industrial Revolution and the working class. Orwell very much disliked mechanization associated with the Industrial Revolution and the generation of a new working class, "swindled by progress". He said that comparatively few people wanted it to happen, and yet it happened. In the 1930s, he saw a continuing army of scientists and technicians marching along the road of 'progress' with everyone else, "panting at their heels." He intensely disliked the way mechanization had dehumanized the working class and he disliked what he viewed as an inevitable mechanized future.

In the 21st century, now 80 years into Orwell's future, we have a much larger army of scientists and technicians worldwide applying the results of engineering and electronics research to change our lives and our world. If Orwell were alive today, would he find that science and technology now are leading us along our desired path, or would he find that we continue to simply follow the path of 'progress' with "the blind persistence of a column of ants"(GO)?

|

Bibliography

Anderson, D, 1975. The Orrell Coalfield, Lancashire 1740-1850 (Moorland Publishing Company, Buxton,Derbyshire, UK).

Anderson, D., Blundell's Collieries 1776-1966. (Wigan Printing, Wigan, UK).

Bankes, J. H. M., 1962. 'A nineteenth-century colliery railway', in Transactions of the Historical Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. 114, 155-188.

Beckett, J.V., 2001. Byron and Newstead; the Aristocrat and the Abbey (University of Delaware Press, USA).

Hannavy, J., 1990. Historic Wigan: Two thousand years of history (Carnegie Publishing, Preston, UK).

Hannavy, J. and Winstanley J., 1985. Wigan Pier: An Illustrated History (Smiths Books (Wigan) Ltd., Wigan, UK).

Hindley Hall Golf Club (http://www.hindleyhallgolfclub.co.uk/?page_id=2, accessed December 20, 2014).

Hughes, J., 1906. Liverpool banks and bankers, 1760-1837 (Henry Young and Sons, Liverpool, UK).

Langton, J., 1979. Geographical Change and Industrial Revolution: Coalmining in South West Lancashire (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK).

Langton, J., 2009. 'Alexander Leigh (c.1683-1772)' in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Leeds and Liverpool Canal Society (http://www.llcs.org.uk/index.html, accessed January 4, 2015)

Clarke, M. Personal communication

Orwell, G., 1937. The Road to Wigan Pier (Victor Gollancz, London, UK).

Sinclair, D., 1882, The History of Wigan, Vol. 2 (Printer and Publisher, Wallgate, Wigan, UK).

Whitaker, `J., 1775. The History of Manchester, 2nd Book (Johnson and Murray, London, UK).

Townley, C.H.A., Smith, F.D. and Peden, J.A., 1991. The Industrial Railways of the Wigan Coalfield, Part 1 West and South of Wigan, Chapter 5, Winstanley and Worsley Mesnes, 85-97 (Runpast Publishing, Cheltenham, UK).

Whittle in Hardwick, C., 1857. History of the Borough of Preston and its environs: in the county of Lancaster (Worthington & CO., London, UK).

Wigan Archaeological Society, Wigan Pier (http://www.wiganarchsoc.co.uk/how.html#Pier, accessed January 2, 2015).

Winstanley, D., 2013. Wigan and Slavery (https://www.academia.edu/4610269/Wigan_and_Slavery, accessed December 12, 2014).

Winstanley, D., 2013. 'The Rise and Fall of Pony Dick' (Past Forward, 62, 20-1, Wigan Heritage Service).

Winstanley D., 2012. The Walking Horse and Clarke's Railway (https://www.academia.edu/5112064/THE_WALKING_HORSE_and_CLARKES_RAILWAY, accessed December 10, 2014).

Winstanley, D., 2014. 'The Evolution of Early Railways in Winstanley, Orrell and Pemberton, Lancashire, England, 1770s To 1870s', in Early Railways 5, edited by David Gwyn (Six Martlets Publishing, Clare, UK), 112-131.

Wikipedia Leeds and Liverpool Canal

|

Notes

1. For half a century, from about 1710 to 1760, Alexander Leigh dominated the borough's administration. He was a lawyer, estate manager and a strong promoter of industry. As an opportunist titan of change, Leigh purchased lands in the Wigan area that contained more than 4 million tons of coal. Leigh also operated collieries on the river, traded coal to the Ribble estuary and the Lancashire coast, and made money from rents on coal yards, wayleaves and coal royalties. In 1721 he purchased Hindley Hall, the old hall and estate lands (Hindley Hall Golf Club). As well as having great business acumen, Leigh is described as domineering, cantankerous and unscrupulous (Langton,Oxford DNB).

Descendants of Alexander Leigh gained local and national prominence, with continuing ties to the Wigan area today. His grandson, Robert Holt Leigh, served as MP for Wigan and was created Baronet Whitley of Wigan in 1815. He inherited Hindley Park from his grandfather and c.1811 built a magnificent hall. Robert died unmarried and in 1843 his estates passed to his cousin, Margaret, who married Robert Pemberton, a London Barrister. Their son, Thomas Pemberton- Leigh, became Baron Kingsdown. In 1855 the mineral rights of the estate were leased to John Lancaster, who formed the Kirkless Coal and Iron Co. Ten years later Lancaster amalgamated his coal company with that of The Earl Crawford and Balcarres to form Wigan Coal and Iron Company. (Hindley Park Golf Club)

Pemberton-Leighs, later Leigh-Pembertons, were ancestors of Robin Leigh-Pemberton, 1st Baron Kingsdown of Pemberton, who served as a Governor of the Bank of England from 1983 to 1993. Around 1982, Hindley Hall and grounds were purchased by membership from Sir Robin Leigh-Pemberton ("Hindley Park, (also known as Hindley Hall Golf Club), Wigan, Greater Manchester, England" https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/hindley-park). Robin Leigh-Pemberton's son, James Leigh-Pemberton, was appointed head of UK Financial Investments in 2013 (Oxford DNB, Wiki RLP and JLP).

2. The stone Arches Viaduct that carried The Walking Horse across Smithy Brook at the Winstanley-Wigan border in 1813 was built in the 1790s to carry a wooden railway and horsedrawn carts (Anderson, 19.., Winstanley 2014). The viaduct was built by Fairclough (personal Communication, Sam Fouracre, 1979).

The Walking Horse hauled coal on John Clarke's narrow-gauge, iron railway from Winstanley down to a pier head on the canal opposite Crooke. When this steam locomotive took over from the horse-powered railway in 1813, The Arches Viaduct became the first viaduct in the world to carry a steam locomotive (Winstanley 2014). Unfortunately, Photo 1 in Hannavy and Winstanleys 1985 book (ref) is not a photograph of a model of the Blenkinsop locomotive built by Robert Daglish. Thomas Scherer's detailed diagram of the Walking Horse can be found in Winstanley (2013; 2014).

3. Alexander Lindsay, the 6th Earl, inherited Haigh Hall and grounds in 1787 when he married Elizabeth Dalrymple, great niece of Sir Roger Bradshaigh. The Bradshaighs had been in residence there since the late 13th century and had profited from the extensive cannel coal reserves in the park grounds. Lindsay saw an opportunity to exploit the iron ore found in the Douglas Valley and established an iron foundry at the bottom of Leyland Mill Lane (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haigh_Hall) . This was not initially successful but later became a very profitable engineering works building steam engines for railways across the country including Brunel's Great Western railway (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haigh_Foundry ).

4. Claughton was an interesting character. Claughton married Maria, the illegitimate daughter of Thomas Legh. Enthusiastic to engage in land speculation, in 1812 he agreed to purchase Newstead Estate in Nottinghamshire, the home of Lord Byron and his ancestors. However, he was unable to complete the purchase and forfeited £25,000. Apparently unable to sustain success, Claughton was declared bankrupt in 1824 (Beckett, 2001). His son, also Thomas, became Professor of Poetry at Oxford University and later Bishop of Rochester and the first Bishop of St. Albans (Wikipedia Thomas Legh Claughton). In 1844, Haydock Lodge was opened as a lunatic asylum and quickly became the largest pauper house outside London (Reverend Noble Wilson, 1845. "Haydock Lodge Lunatic Asylum" http://studymore.org.uk/ahaydock.htm; Roberts, A., 1990. "England's Poor Law Commissioners and the Trade in Pauper Lunacy 1834-1847", http://studymore.org.uk/mott.htm).

5. A measure of the Bankes family wealth in the 19th century is that they purchased an 80,000 acre estate in Scotland and other estates in England. They also had their own yacht in Liverpool, landscaped Winstanley Estate, including 'the long wall', and enlarged Winstanley Hall. Letterewe Street in the Potteries area was named after Bankes' estate in Scotland and Eleanor Street is probably named after Eleanor Starkie, Meyrick Bankes Jr's wife, or their daughter Eleanor Starkie Letterewe Bankes. This is the same Starkie (Starkey) family who owned the cartwright business and inn at Pony Dick (Winstanley 2013 PF).

6. Bryan Blundell's ships are reputed to have been the first in Liverpool's dock when it opened in 1715. Like many Liverpool merchants, the Blundells amassed considerable wealth from the slave trade (Winstanley 2013, 2014). It was Jonathan Blundell's wealth and business acumen that were the start of the Blundells' coal business in Orrell in 1776 and Pemberton Colliery some 40 years later (Anderson - Blundells; Anderson - Orrell CF).

|

|